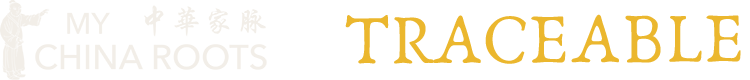

Journalist Stephanie Ho has dedicated most of her adult life to uncovering the stories of her ancestors. As the daughter of the first Chinese-American to graduate from the U.S. Air Force Academy, she grew up around air bases feeling rootless and out of touch with her heritage. Guided by journals and trips back to China, Stephanie now shares her journey to reconnect with her great-grandfather, Fung Chien, the first Chinese man to travel to the North Pole.

Photo: B Lucava in Tromso, Norway

I often wonder what Fung Chien would think about me, his great-granddaughter. Knowing what I now know about him, I wonder if who I’ve become was inevitable.

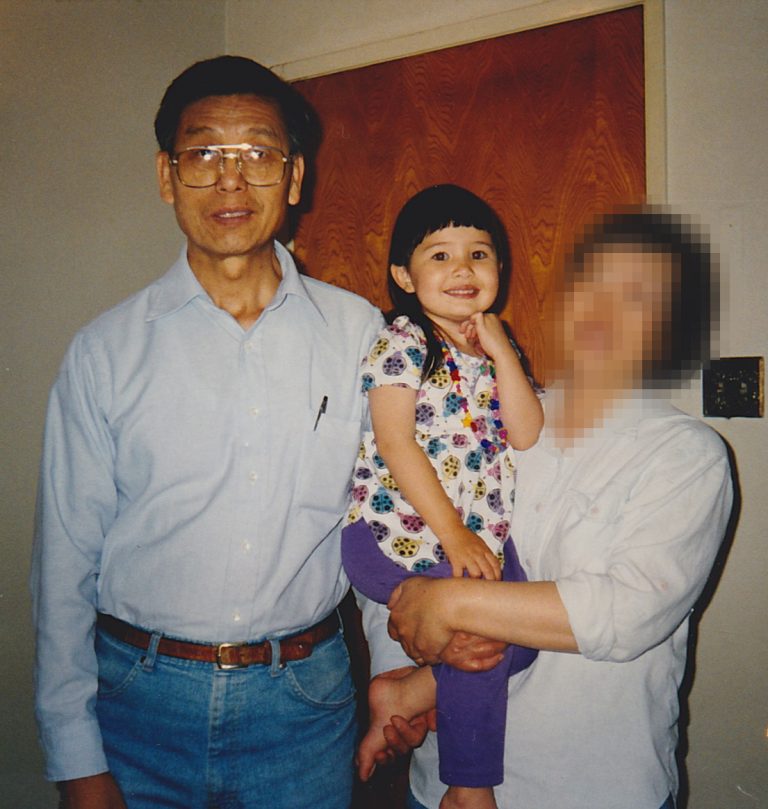

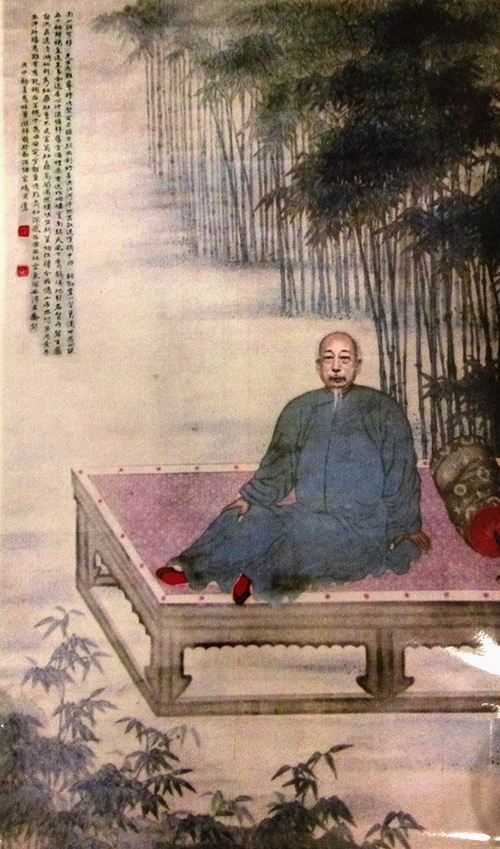

Fung Chien was the first Chinese to travel to the North Pole. A scientist at heart, he was also the director of China’s shortwave broadcasting station, known as the Voice of China, which operated out of a cave in Chongqing during World War II.

I did not know about him when I chose my career as a journalist. Even though I was born three generations later in the United States, I apparently couldn’t help but follow in his footsteps. For over twenty years, I worked as a reporter for the main U.S. shortwave broadcaster, the Voice of America, spending half that time on two tours as the VOA correspondent in Beijing.

I think Fung Chien would be amused to know how alike we are. Like scientists, journalists always want proof. I am always asking questions, always on the lookout for new information. As I spent more and more time telling other people’s stories, I increasingly felt the need to answer a basic question for myself too — namely, who am I? I needed to know more about where I came from.

When I started looking into my family history, I was amazed at what I found, but quickly became overwhelmed by the sheer wealth of material. I had studied Chinese language and history in college, but trying to navigate boxes of historical documents and track down relevant leads on my own? I felt way in over my head.

It was my conversations with My China Roots that brought clarity and organization to my otherwise unruly project. MCR’s researchers knew just the right questions to ask to help me plan my investigation. Their timely guidance included strategic avenues I hadn’t even thought of or known about before.

My research began with another great-grandfather on my father’s side. I learned that Cheng Shianglin was the Qing dynasty salt tax collector for a huge swath of southern China. His prosperity was evident in that he could afford to have five wives, each with separate quarters, in a huge family compound in Hunan province. He was 66 when his youngest wife gave birth to my grandmother Cheng Yin-Hwa. Her only memory of her father was the way his silver hair shone in the sunlight when he sat in the courtyard, having it combed out.

I visited that family compound twice: once in 1994 and the second time in 2013 with an uncle who was born there. He was speechless with shock as we walked around the dilapidated structures. Many buildings had been repurposed to house farm animals, while others were simply left to decay. My uncle struggled to reorient his memories of home to the crumbling ruins, now overgrown amidst the rice paddies.

If my Qing Dynasty ancestor represented old China, Fung Chien represented new China.

After World War II, China’s Nationalist government sent Fung to Paris in August 1947 to represent China at a UNESCO meeting. After the conference, he took advantage of his situation and, according to family lore, used his per-diem money to go to Longyearbyen, Svalbard Island, Norway, which was, and still is, the northernmost city in the world. He told everyone he was going to the North Pole to research the effect of the Arctic atmosphere on radio waves from his beloved Voice of China. But, I suspect, his real goal was to see the Northern Lights.

To reach Longyearbyen, Fung bought passage on a Norwegian coal ship. It seems he left quite an impression, based on a surprisingly detailed account I found in the memoir of Liv Balstad, the wife of the governor of Svalbard.

“Hardly had the vessel sailed to the south, when a new guest appeared… a strange figure in a floor-length sheepskin coat and boots. … He was a fascinating character. His eyes were gentle and quiet, and when he spoke, it was almost like he was singing.

Liv Balstad, NORD FOR DET ØDE HAV (North of the Desolate Sea, 1958)

It had been impossible to get him cabin space, so he had to lodge in the coal bunker with the Norwegian miners. I have heard that the China man settled in without a murmur, and even declared that he had never had a more interesting journey. Several workers spoke English, and he was full of praise for how helpful they had been.

When he arrived, he had only a few light leather shoes, which of course were full of mud… There were no rubber boots that fit him, but eventually the problem was solved when he borrowed some boots that belonged to a schoolboy who was away on vacation. Fung Chien thought it was wonderful footgear. He obviously had little desire to part with them, so in the end, he kept them and the schoolboy got new ones.”

Reading these passages, I can feel his sense of adventure and wide-eyed wonder. Fung Chien was farther north than any Chinese person had ever been before. With the moon visible in the sky all day, I can imagine him looking up from the ship’s deck, comforted to see something familiar. Perhaps the sunlight glinting off the glaciers reminded him of a Li Bai poem he had learned as a child:

Before my bed a pool of light–

Can it be frost on the ground?

Looking up, I find the moon bright;

Bowing, in homesickness I’m drowned.

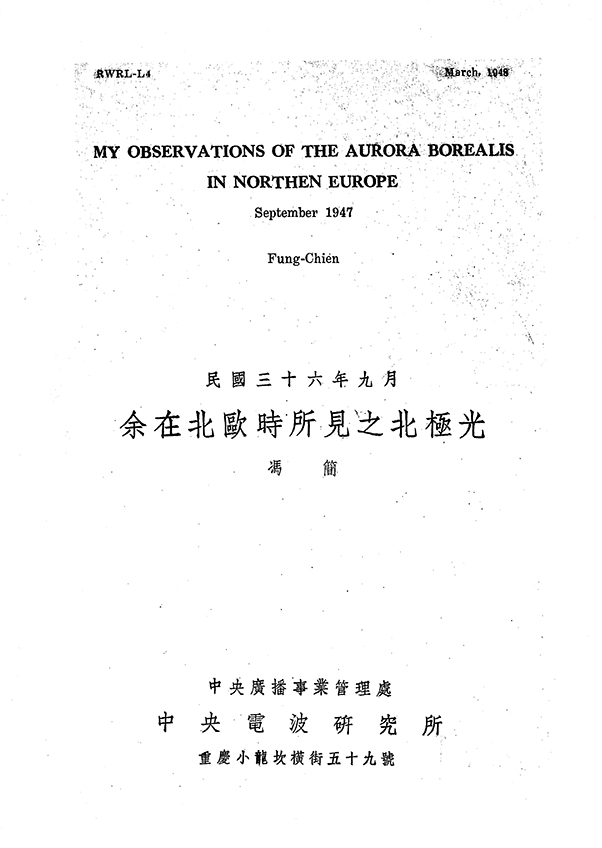

North of the Arctic Circle, Fung found that radio reception for the Voice of China was far worse than in Oslo, where residents had sent him letters confirming the reception was good. However, that did not dampen his spirits, since he got to witness the aurora borealis not just once, but several times.

In his journal, Fung wrote that his favorite was the drapery aurora, a scientific phenomenon that created the impression of green or yellowish-white lights rippling like a dancing curtain across the vast sky. The Northern Lights were likely the most majestic, beautiful, awe-inspiring and humbling thing he had ever seen in his life.

Fung returned to China richer for his experience. In 1948, he produced a scientific report, “My Observations of the Aurora Borealis in Northern Europe,” which was a reflection on what, for him, was the true highlight of his time abroad. For this man of science, it may have been the closest he would ever get to having a religious experience.

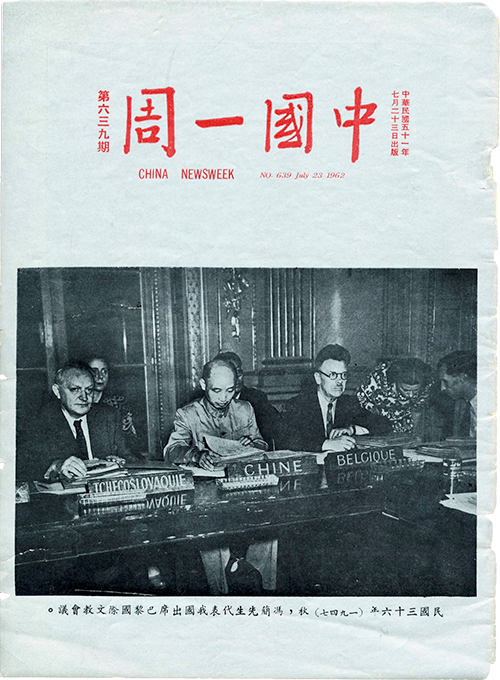

Fung Chien, the modern intellectual, passed away from a sudden heart attack late one night in 1962, exiled in Taipei, where the Nationalist government fled after losing the Chinese Civil War to the Communists in 1949. He always believed he would return to China, but he didn’t live to see that day. Instead, he is buried in Taipei at the Yangmingshan First Cemetery.

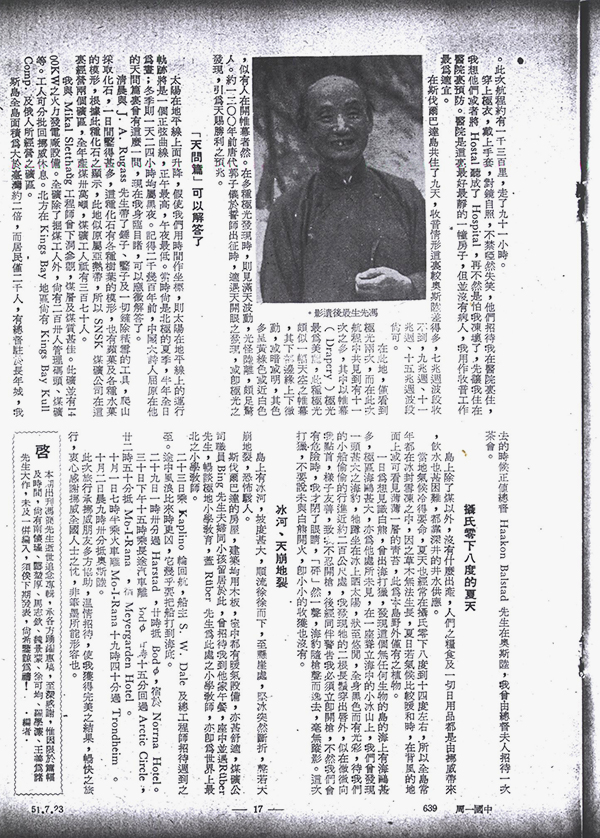

In eulogies published in China Newsweek, one friend recalled Fung’s playful and self-deprecating humor. He pointed to one speech where Fung brought the house down with laughter by describing the aurora borealis as a bunch of colorful fairies attracted to a handsome man.

The confines of Chinese tradition were not enough for his restless heart, and this is something I can relate to.

Fung’s departure left a gaping hole in my mother’s life. She has fond memories of growing up in his household — first in Chongqing, then later in Taipei. In contrast with the stern silence of her elegant grandmother, her grandfather always had a warm smile for her.

I gave little thought to her stories until 2010, when I brought her to see the statue of him that now stands in the heart of Chongqing University, where she had grown up decades ago. The inscription calls Fung Chien a “radio expert” and “friend of the university,” honoring him as the first Chinese to go to the North Pole in 1947 to research the effect of the Arctic atmosphere on radio waves. When she saw the statue, my mom’s face beamed with a pride I had never seen before.

Compared to Fung Chien, little is known about the kind of person Cheng Shianglin was. Personally, knowing this august figure is in my family tree offers some fulfillment of my childhood wish to have been descended from British royalty. However, as far as I know, the Venerable Cheng was not memorialized for his keen intellect or other skills that matter to me in the 21st century.

In the end, I feel that I identify more with Fung Chien, the man of science who wanted more. The confines of Chinese tradition were not enough for his restless heart, and this is something I can relate to. From the remnants of my father’s roots in Hunan, to a statue of my mother’s grandfather in Chongqing, I have looked into family history I didn’t understand, and returned with renewed context for why I am who I am.

While I did not know my great-grandfathers, perhaps their commitment to tradition and curiosity have been in my blood all along. What would they think of me, their great-granddaughter, who is using what they have given her, to make her way as best as she can?

Find your ancestral village and connect with Chinese relatives!

If you are interested in finding your ancestral village and connecting with relatives in China, we would love to be of assistance. Our global team of researchers has helped hundreds of families discover their Chinese roots. Learn more about our services or go ahead and get in touch!

With the global pandemic, My China Roots is offering virtual tours packaged with our research trips to your ancestral village. Check out a demo here!