As third-generation Chinese-Australians, Dennis and his two brothers often heard their parents emphasize the importance of speaking Chinese and knowing their family history. But what was the point? Chinese culture felt irrelevant to life in Melbourne — and was even less so after their grandfather passed away when Dennis was only eight.

“I really didn’t appreciate I was Chinese until I started shaving,” he recalls. “Standing there looking in the mirror, I saw a stranger, an alien face.” As far as 14-year-old Dennis was concerned, looking Chinese was only an invitation for unwanted attention.

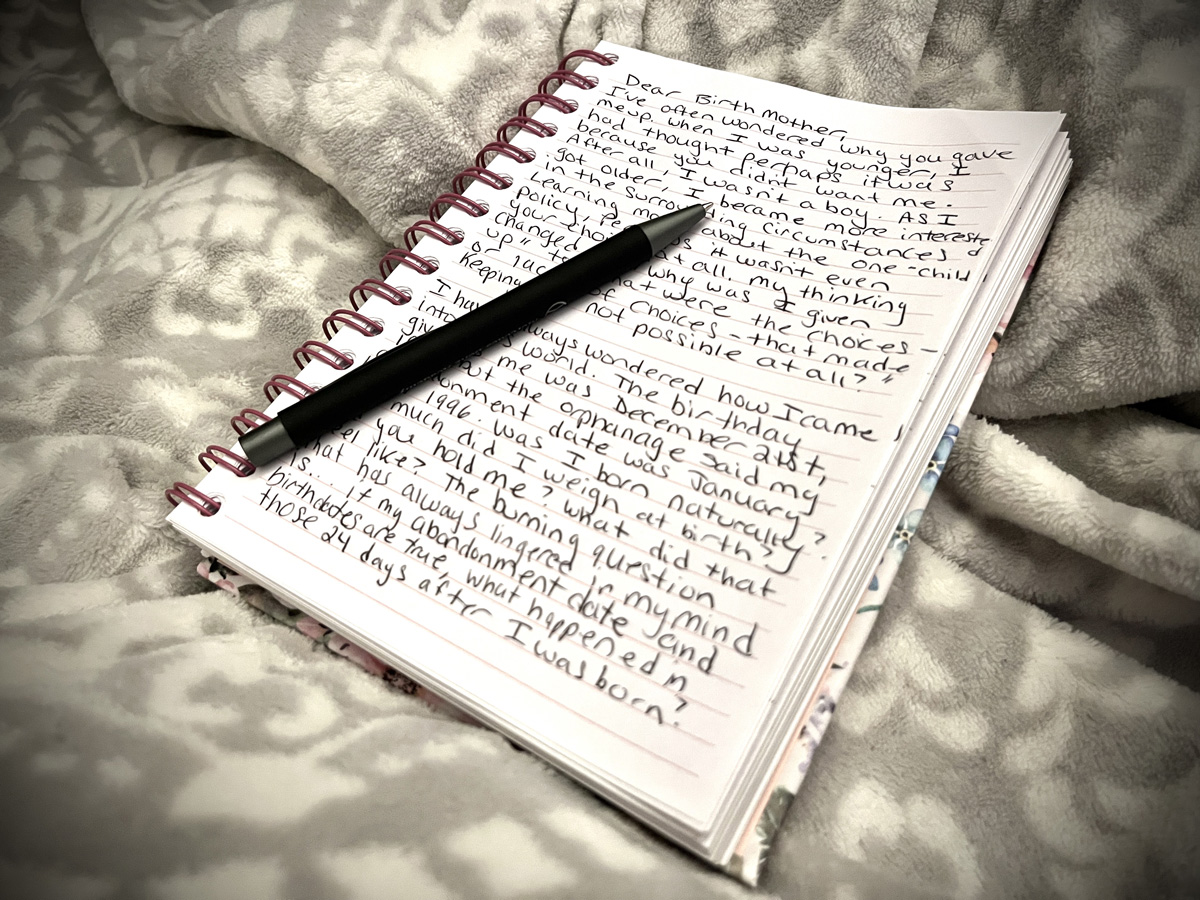

It wasn’t until half a century later when Dennis became the proud grandfather of four beautiful, multiracial grandchildren that his parents’ words began to resonate. As the eldest of the three brothers, he felt a moral duty to ensure their descendants would be able to connect with their Chinese heritage.

“At a family gathering, I informed my brothers that I was committed to go to China to try and find our ancestral records, and document everything we knew for future generations of our family in Australia. They committed to join me in the search!”

As a starting point, the Yeung brothers turned their attention to two key records in the family.

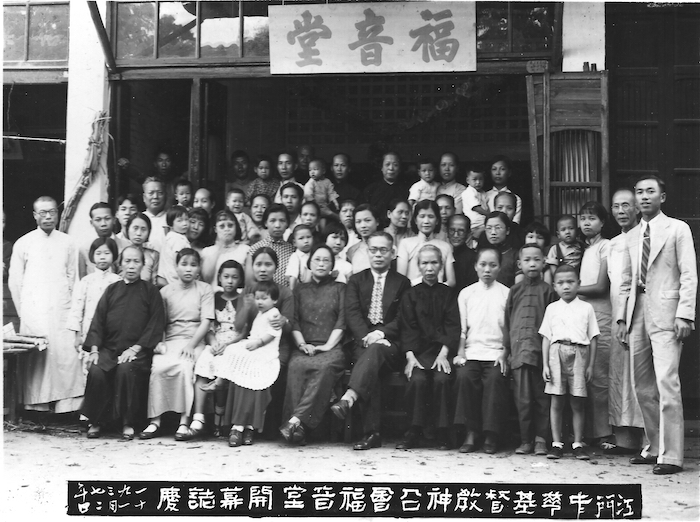

First was a booklet detailing their grandmother’s life as a missionary, written by an uncle during the 1970s. It revealed that their grandmother Mary Chen, an Australian national whose father migrated from China in the 1850s, had met their grandfather Chick Nam Yeung, a Presbyterian minister from Guangdong, while doing missionary work in the Pearl River Delta — the home of most Chinese immigrants to Australia.

Due to the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), they fled to Hong Kong in 1938, then repatriated to Melbourne together. After the war, they returned to continue their missionary, building orphanages for war orphans in Hong Kong.

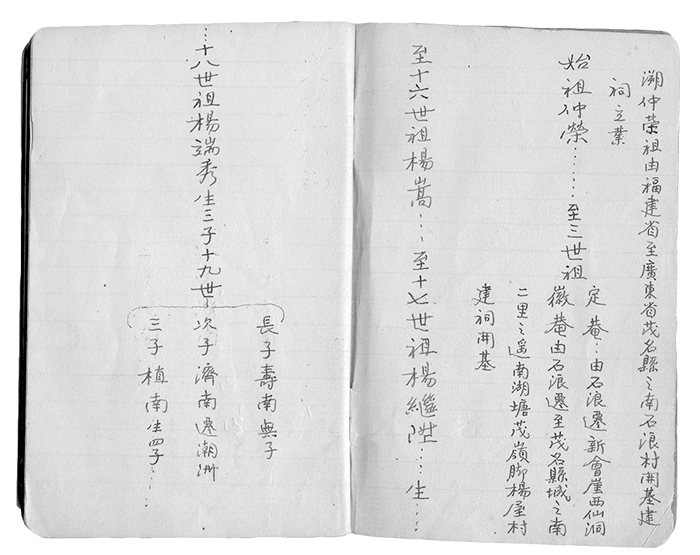

Second was a handwritten entry in their grandfather’s notebook, tracing 21 generations of Yang ancestors back to the village of Shilang in Maoming, Guangdong.

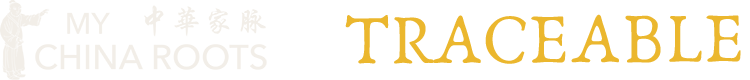

According to their father, their grandfather had corresponded with a villager in Gaozhou to add their family to the clan zupu, a traditional genealogy record of family trees and migration histories. However, this was before the Cultural Revolution, when many ancestral records were destroyed as relics of the past. Could their Yang zupu have survived?

Keen to find out, Dennis got in touch with My China Roots to investigate the fate of his family’s zupu. Upon visiting Gaozhou, our researchers found a zupu with an exact match for his grandfather’s name. However, upon closer inspection, this Chick Nam Yeung had a different set of siblings and children, belonging to another branch of the clan.

With their zupu still to be found, the Yeung brothers lost no time booking their highly-anticipated trip to China with MCR. Over a whirlwind two weeks, they made plans to visit the missionary schools that their grandfather had likely attended in Guangzhou, travel to his village in Gaozhou, and also try to locate their mother’s village in Jiangmen. According to their dad, she had grown up in a village possibly named Beisheng, somewhere 100 km south of Guangzhou.

“When she was only five or six, our mother moved out of her home into the village dormitory where children were schooled and cared for, while their parents farmed the fields,” Dennis shares. “As we ambled around, wondering where her village could be, our MCR guide stopped to ask a lady randomly passing on the street. By pure chance, she knew exactly where Beisheng was, and even walked us the full 1.5 km of the way there!”

This watershed moment wasn’t the only surprise in store.

The next day, the brothers paid a visit to Shilang, which, according to their grandfather’s notes, was the village of the earliest Yang ancestor in the province. There, they met with delegations from the Maoming Federation of Returned Overseas Chinese and the Maoming Yang clan association. Among them was the elderly keeper of the wider clan’s genealogy records.

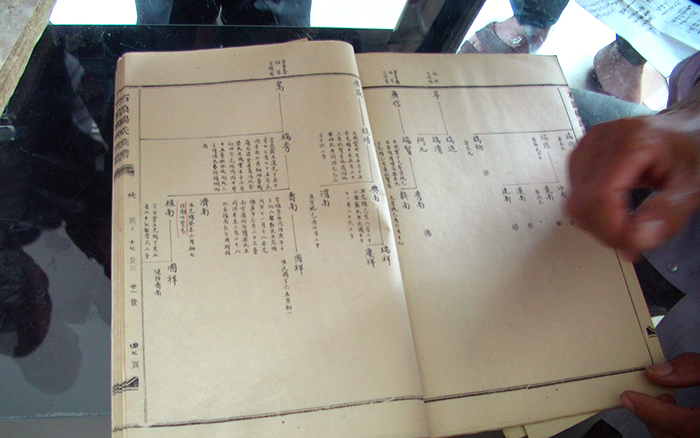

Against all odds, he had a zupu that not only matched the generations outlined in Chick Nam Yeung’s notebook, but also traced all 21 generations back to the clan’s founding ancestor. The family’s zupu had indeed survived, thanks to a brave clan member who hid it away before it could be destroyed!

Finally, it was time for the brothers to behold their long-lost zupu. Its delicate pages held the names of their branch of the Shilang Yang clan — and sure enough, on page 47, lay the names and birthdates of their grandfather, great-grandfather, and great-great-grandfather.

“When I saw their names right there on the page… it was, simply put, truly magical,” Dennis recalls. “The link to our family heritage was restored. That single breathtaking moment made everything — all the work, all the anxiety, all the energy — completely worthwhile. The only experiences I can compare it to are my wedding and the birth of my children!”

Now back in Australia, Dennis can’t wait to share their adventures with his grandchildren, as they become more curious about their multicultural roots.

“Bright, feisty — they’ve got the whole world in front of them!” he says. “Now our descendants have an entry point to go further in connecting with their Chinese heritage if they wish. That’s why I took on this mission.”

Find your ancestral village and connect with Chinese relatives!

If you are interested in finding your ancestral village and connecting with relatives in China, we would love to be of assistance. Our global team of researchers has helped hundreds of families discover their Chinese roots. Learn more about our services or go ahead and get in touch!

With the global pandemic, My China Roots is offering virtual tours packaged with our research trips to your ancestral village. Check out a demo here!