When it comes to tracing your Chinese family history, written records don’t always tell the full story. Between the exclusion of women from traditional family tree books (known as zupus), and the fabrication of family ties to sponsor “paper sons” entering the United States, there may be more to your family tree than meets the eye. If you are lucky enough to have living elders, make it a top priority to interview them while you still have time.

“But what if my Chinese isn’t good enough to do an interview? What if they don’t feel comfortable opening up to me? What if… ” Yep, I’ve been there. Curiosity is a beautiful thing, but it’s not always welcome or rewarded in Chinese culture. Interviewing your Chinese-speaking relatives takes great patience, cultural sensitivity, and historical awareness. Most importantly, it takes a combined team effort with your family to navigate language and cultural barriers.

Before you interview your Chinese-speaking relatives, ask yourself these four essential questions to make the most of your conversations. Taking the time to prepare in advance will help you unearth the stories of your ancestors with wisdom and respect.

1. Rally Your Tribe: Whose stories are you most curious about?

Let’s begin with the storytellers who already pique your interest. Who intrigues you? Who would you like to get to know better in your family tree? If you could share a meal with one ancestor, who would you pick? Why?

Write down any names that come to mind. If you don’t know their name, write their familial role or relationship to you. If they are no longer around, who might be able to tell you more about them? Jot down their names too.

If your family is anything like mine, you may have relatives spread out all over the world. Before you start worrying about travel or language barriers, remember that you don’t have to enter these conversations alone. Within your own family, look for one of these relatives to help you get global and local:

- Open Books: Start with the natural talkers. They love recounting tales of the past, especially for the younger generation (bonus points if they’re not camera shy). Interviewing willing relatives first, even if they’re not as knowledgeable, can build a ripple of trust, showing more hesitant relatives what to expect if they sit down with you.

- Branch Connectors: Reach out to the family member who’s made an effort to keep in touch with everyone. Often the eldest, they’re responsible for organizing family reunions. They likely keep a spreadsheet updated with contact info and have access to WeChat or WhatsApp groups for each branch. Want to interview a distant relative in a Chinese village or Australian suburb? They can hook you up in a heartbeat.

- Fellow Historians: Has anyone else besides you caught the family history bug? Perhaps an aunt in California has kept records over the years. Or your cousin in Singapore is keen to interview nearby relatives. Invite them to share their questions and findings with you. You can cover more ground by working together.

Now you have a starting list of people to not only interview, but partner with as well. It’s okay to start small. As you have more conversations, you will naturally pick up clues leading you to more storytellers. Whenever possible, ask your family for sources and referrals: “Can you tell me more about who might know that?”

2. Educate Yourself: What history has your family lived through?

Before you sit down for an interview, take the time to understand the historical context of your relative’s life, through free resources like the Immigrant History Initiative. From the tumultuous Cultural Revolution to the xenophobic Chinese Exclusion Act, the history of Chinese immigration is fraught with traumatic events resulting in family separation, struggle for survival, and – as you may encounter – silence about the past. The more informed you are, the more prepared you’ll be to ask follow-up questions and offer compassion when difficult memories resurface during the interview.

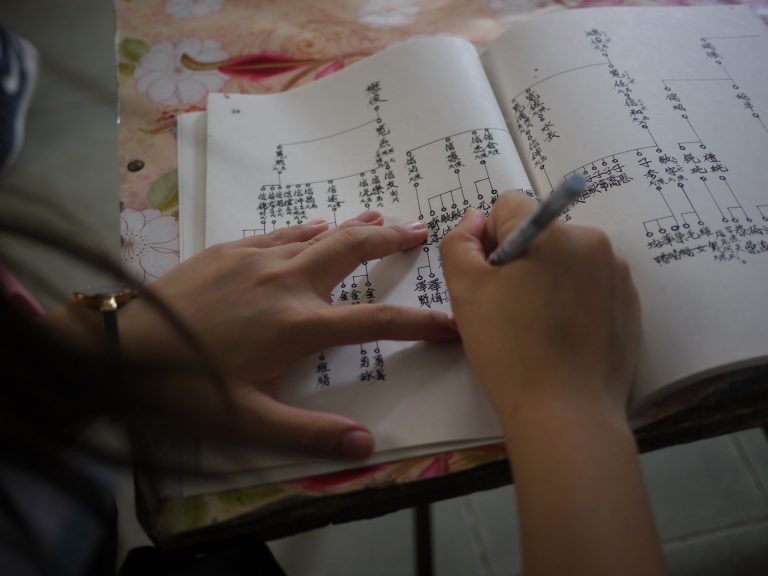

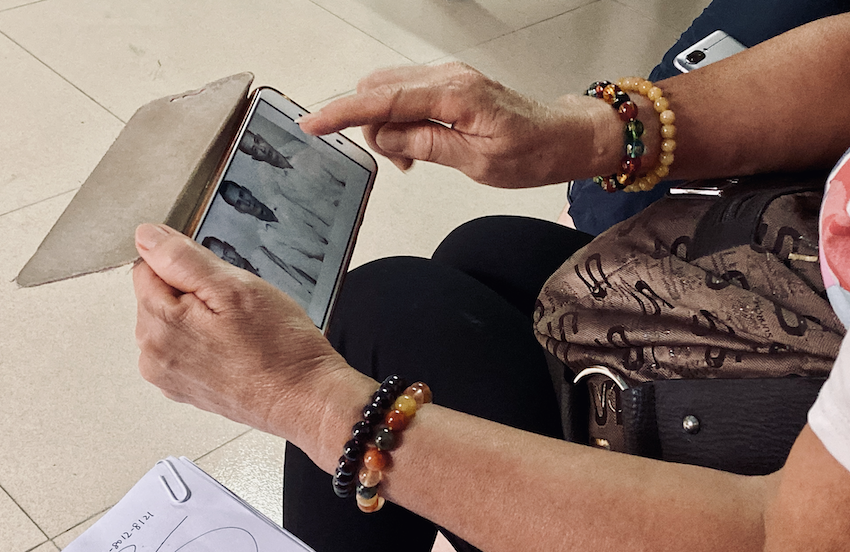

You can use visual cues like a photograph or handwritten family tree to jog your relative’s memory. To get the conversation going, you could ask them to retell a story you know they love telling. You don’t know what you don’t know, so it can help to start from the very beginning and go chronologically. Once you have the big picture, you can ask specific questions to fill in the gaps.

If your relative is reluctant to share, be gentle, patient, and move at their pace. Do not take their silence personally, especially on topics like racism, infidelity, opium use, lawbreaking, political collusion, and suicide. Chinese elders often carry a deep sense of shame for past struggles and stay silent to protect the next generation from the pain they endured. While storytelling has the power to heal, “reopening the book” can be re-traumatizing if their grief has not been acknowledged or processed yet. For some, the act of interviewing can bring back memories of harsh interrogation during immigration checks and citizenship tests. Cultural beliefs around hierarchy, patriarchy, and class can also cause some elders to be self-effacing, claiming that their story does not matter.

Take this challenge as an opportunity to show love and care to your family member. Assure them that you are simply here to listen and understand, without any judgment. Tell them you are proud of them and admire their resilience. Emphasize the good that will come from sharing their story for future generations. Knowing what their ancestors overcame to get to where they are, their descendants will inherit a strong connection to their family roots.

As relatives become more comfortable opening up, listen for language referring to changes in lifestyle, location, and mindset. Relatives who lived through the Cultural Revolution may say things like “we used to have…” or “we used to do…” Listen too for milestones like “he was the first to leave the village…” or “they were the only ones to send back money from…” You can map these clues to a historical timeline for a much clearer picture of who was where when and how they felt the personal impact of world events.

3. Archive Your Findings: How will you record and organize your family history?

Once the stories start flowing, ask your family for permission to record your conversations. Be clear about your goals. What will these recordings be used for (ensuring accuracy, educating the next generation)? What is your vision for the end product (reunion video, family history book)?

If your primary audience is family, consider setting up cloud storage for relatives to access copies of the recordings. If you intend to share the content publicly (e.g. published article or film project), be transparent and ask your relatives to sign consent forms approving your use of the interviews.

If your relatives feel comfortable being recorded, you could set up a camera on a tripod next to you during the conversation. However, audio quality should always be prioritized. The glossiest 4K footage cannot replace the authenticity of a human voice. Personally, I like to use a Zoom H1n portable recorder with a clip-on lapel mic and gaffer tape to secure it on clothing. It’s a subtle, no-fuss setup you can place in view on the table to help them get accustomed to being recorded.

As you record more conversations, our free family tree builder can help you synthesize your findings. You can update your family tree with new relatives (Chinese names supported), and organize photos, recordings, and interview notes connecting the dots between your ancestors. At any time, you can cross-check your family tree for more record matches in Our Roots Database, the largest collection of digitized genealogical records for overseas Chinese in the world.

4. Cross the Gap: Who can help you navigate cultural barriers?

You might find yourself in situations where it’s not ideal for you to be the one to conduct an interview. Perhaps your relatives happen to speak one of the 300+ languages in China that you aren’t fluent in. Or maybe you discover “bad blood” between your branch and another branch of the family, so they aren’t interested in talking with you.

To cross language and cultural barriers, find a translator to help you communicate and build trust. It’s important that they’re not just linguistically fluent, but also culturally fluent in the local customs and attitudes. For me, my Mandarin is at the level where I can ask a question, but I will understand only half of the response. When I had a chance to get dinner with relatives in Beijing, I brought a Chinese American friend with me to translate for us. She picked up on cultural jokes and historical references I would have missed, and the experience brought us all closer together.

If you don’t have a friend or family member to assist you, our team of trained interpreters in China can help you navigate your next conversation with ease. If you need a translator, we can conduct an interview on your behalf, or even facilitate an online reunion for you with your Chinese relatives. No matter where you are in your roots search, we would love to bridge the gap and help you connect more deeply with your family.

What advice or challenges do you have when conducting family history interviews? Let us know in the comments below!

Find your ancestral village and connect with Chinese relatives!

If you are interested in finding your ancestral village and connecting with relatives in China, we would love to be of assistance. Our global team of researchers has helped hundreds of families discover their Chinese roots. Learn more about our services or go ahead and get in touch!

With the global pandemic, My China Roots is offering virtual tours packaged with our research trips to your ancestral village. Check out a demo here!