Tombstones (also called gravestones or headstones) are a highly valuable source of information for researching your Chinese family history. Bilingual tombstones are especially key to discovering the identities and ancestral homes of immigrant ancestors, such as the original Chinese characters of their name and their village in China.

If you cannot read Chinese characters, don’t be intimidated! Like the anatomy of the human body, each tombstone is both unique and reflects universal patterns in its design. By the end of this article, you will have a keener eye to make sense of the clues on a Chinese ancestor’s tombstone, without needing to be fluent in the Chinese language.

Read on to learn…

- How Overseas Chinese cemeteries honored the roots of early Chinese immigrants

- What types of clues and stories are typically recorded on a bilingual Chinese tombstone

- How to find the tombstones of your ancestors – and make new discoveries with them!

The Origins of Overseas Chinese Cemeteries

According to Chinese tradition, it is believed that one’s bones should rest in one’s ancestral homeland. No matter how far they traveled, many of the earliest Chinese immigrants held this belief that they would eventually return home to China one day.

However, not all were able to complete this journey within their lifetimes. Many immigrants relied upon clan associations to oversee the repatriation of their bones back to China after their death. From around the world, bone boxes were sent to the Tung Wah Coffin House in Hong Kong, then shipped to their ancestral village in China. Yet once the Chinese Communist Revolution began in 1949, this repatriation process was halted. To this day, Havana Chinese Cemetery still has niches filled with bone boxes that never made it back.

In addition, clan associations played a pivotal role in securing burial grounds for Chinese immigrants who died outside of China. In the Americas, many were barred from being interred in Christian cemeteries. To honor their dead, clan associations took initiative to raise membership funds to purchase land for burials, establish their own cemeteries, and cover burial costs.

Today, families across the Chinese diaspora continue to reunite and pay respects at their ancestral graves during holidays like Chinese New Year and Qingming (Tomb Sweeping) Festival.

When you have a chance to visit the grave of an immigrant Chinese ancestor, take photographs and pay close attention to their resting place. What do you notice about the cemetery they’re buried in? What types of people surround your ancestor? Do they seem to have anything in common with each other, such as the same surname or village in China?

Noticing these context clues can help you shed light upon the origins and community ties of your immigrant Chinese ancestor. Here are some examples from the My China Roots Database of the kinds of stories that cemeteries can tell us:

- Hoy Sun Ning Yung Cemetery and Sam Yup Cemetery (California): Most people buried in these cemeteries share the same geographic origins, hailing from Hoisan (Taishan) or Sam Yup, the three counties of Nanhai, Panyu, and Shunde in Guangdong province.

- Kwong Hou Sua Teochew Cemetery (Singapore): Piecing together tombstone inscriptions and physical artifacts found on-site, historians have been able to reconstruct the lives of early Teochew immigrants to Singapore, including elites who held official positions under the Qing government.

- Cementerio Presbítero Matías Maestro (Peru): Some tombstones, like the two below, can reveal an ancestor’s membership or affiliation with an organization or secret society that likely sponsored their burial.

How to Read a Bilingual Chinese Tombstone

Chinese tombstones come in all shapes and sizes. Depending on where in the world your ancestor is buried, their grave may be simple or ornate, bilingual or fully romanized. Graves in Southeast Asia tend to be inscribed completely in Chinese, while graves in the Americas tend to be bilingual (English and Chinese, or English and Spanish).

If your ancestor has a bilingual tombstone…

Be aware that Chinese inscriptions tend to provide much more detailed information than English inscriptions, so they are always worth translating. If you would like professional help to translate your Chinese genealogy records, please check out our translation services.

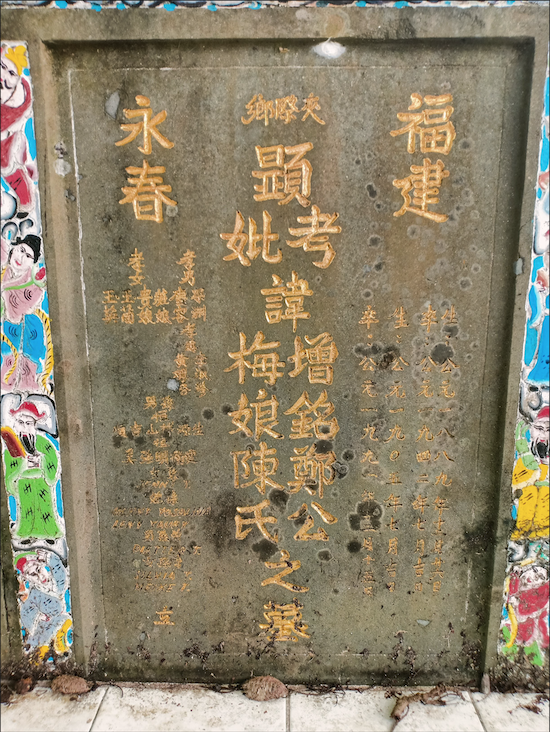

A traditional Chinese tombstone is typically divided into 3 columns. The inscriptions should be read from top to bottom, right to left, and often include:

Surname

If you see Shi 氏 on a woman’s grave, this character indicates her maiden name, while the character 门 (meaning “door”) denotes her married name… perhaps a nod to the door she has crossed from her father’s house to her husband’s house.

Some Chinese tombstones record both the maiden name and married surname. As seen in the example above, 伍门 indicates Wu 伍 is her married name, while 許氏 indicates Xu 許 is her maiden name. However, it is unfortunately much less common to find the first names of women ancestors recorded on their tombstones.

💡 Tip for Identifying Paper Ancestors:

For North American graves, if the Chinese surname looks or sounds significantly different from the Romanized surname, it may indicate that the ancestor may have been a paper son or daughter.

As illustrated in this example, we suspect that the Romanized surname Choy may be an adopted name, while the Chinese surname 劉 (pronounced Liu) may be the true family name. In our experience, it is not uncommon for this discrepancy between the inscriptions on a bilingual tombstone to be the only way to find out the true biological family history of a paper ancestor.

First Name(s)

Including generation names (zibei 字輩), courtesy names (zi 字), pseudonyms (hao 号), and taboo names (hui 讳)

It is more common for graves in Mainland China and Southeast Asia to list alternate names or aliases that the ancestor went by. Learn more about Chinese given names.

Dates of Birth and Death (or Burial)

Dates on older graves tend to follow the lunar calendar, years of an emperor’s reign, or Republican (Minguo) calendar. Learn how to convert Chinese dates.

Ancestral Home

North American graves tend to record the exact village (e.g. Luoxi village, Lianhua town, Tong’an district, Fujian province), while Southeast Asian graves tend to record only the county or district (e.g. Tong’an, Fujian). In contrast, mainland graves seldom record the birthplace, as people are traditionally buried in their ancestral home.

Due to patriarchal customs, it is common for the tombstone of a Chinese woman to list her husband’s ancestral village instead of her own village. While this can be helpful for tracing her husband’s lineage, please keep this drawback in mind when researching women in your family history.

Generational Context

Some tombstones may include the names of descendants (sons 子, daughters 女, grandchildren 孫), a commemorative tribute or biography, and the generation number 世 (mostly mainland graves).

How to Find Tombstones of Chinese Ancestors

If you don’t know where your ancestors are buried, or you don’t have access to visit their graves in person, there is still hope. In partnership with cemeteries and community members across the Chinese diaspora, thousands of tombstones are being photographed and preserved on the My China Roots Database for generations to come.

To find tombstones for your family, all you have to do is follow these 3 steps to connect your family tree to the My China Roots Database:

1. Create a family tree for free on My China Roots.

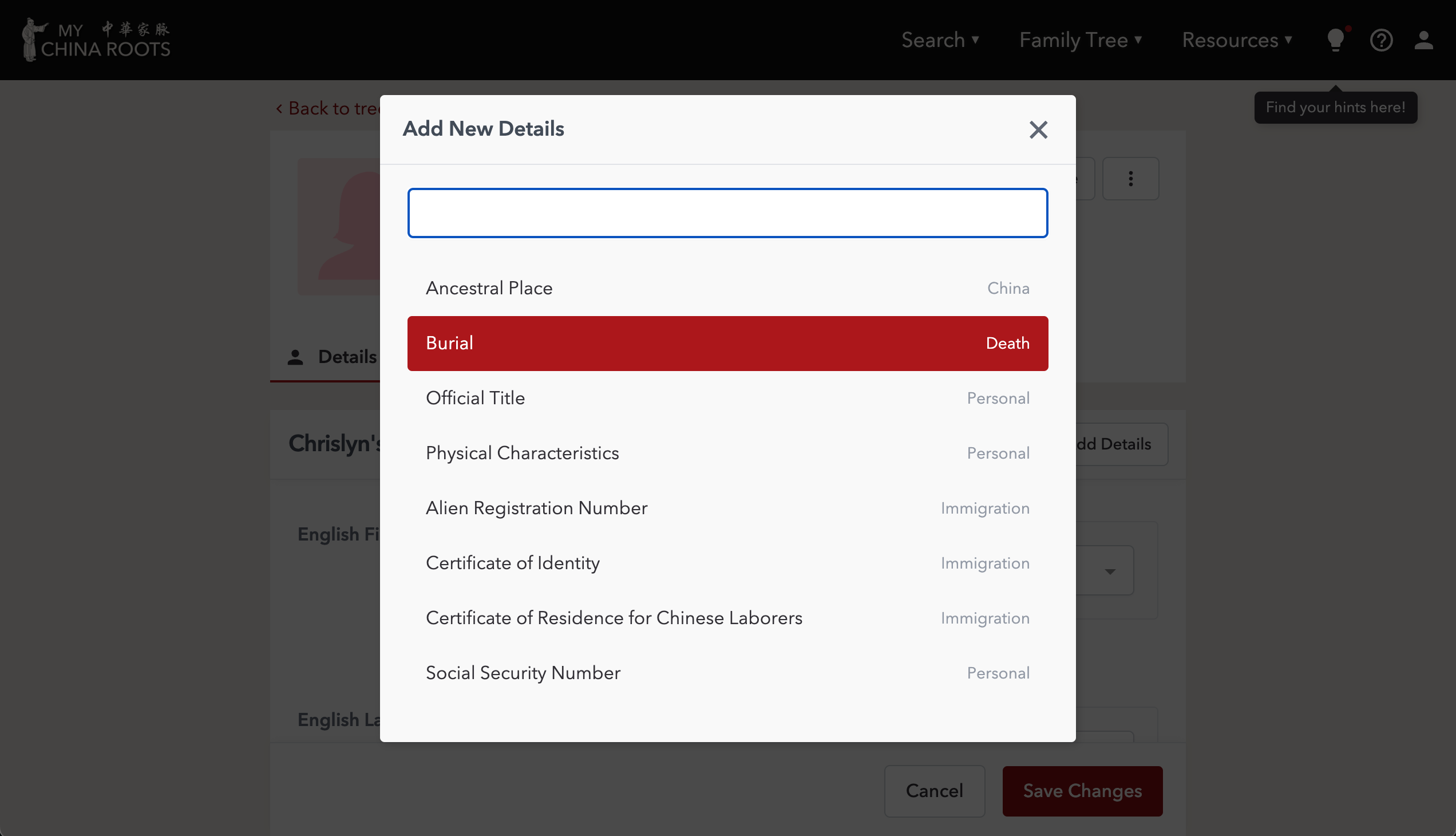

2. Add a family tree profile for each ancestor you’re looking for.

💡 Tip: Fill out as much information as you can under Full Profile > Edit, especially the fields below. The more details you add, the better your chances of finding a tombstone for your family. If you’re not sure, share your family tree with relatives and ask them to help!

- Any available Names in Chinese characters and Romanized letters

- Birth Place (appears under Birth)

- Death Place (appears under Death when Status is set to Deceased)

3. Keep an eye out for a Hint Discovery email from us.

As you update your ancestors’ profiles, we will automatically cross-check your family tree for you with new records added to the My China Roots Database each week. When we find a relevant record matching the information in your ancestors’ profiles, we will immediately notify you so you can personally review the record.

To receive Hint Discovery emails, please check your Account Profile and make sure “Record Matches” is turned on under your Email Notification Settings.

If you’ve already found a tombstone…

Great! In addition to the fields noted above, update your ancestor’s profile with the burial information you’ve learned to find even more records painting a fuller picture of their life, such as immigration case files, censuses, community records, and more.

- Burial Place (appears under Full Profile > Edit > Add Details)

- Ancestral Place (appears under Full Profile > Edit > Add Details)

All in all, tombstones can help you unearth the origins of your ancestry in China, rooting us in collective remembrance and gratitude for the strong bonds of kinship our immigrant Chinese ancestors forged with each other to stay connected to our roots.

As you explore your ancestral past, don’t hesitate to reach out to support@mychinaroots.com at anytime with your questions, feedback, or bug reports. We are all ears to hearing how we can better help you bridge the language barrier and fill in the gaps of your family history!

Make automatic family history discoveries

Need help translating your Chinese records? We would love to help you decode and contextualize your ancestral clues. For over a decade, our genealogy researchers at My China Roots have guided countless families to reconnect with long-lost stories and relatives. Get in touch to uncover your family history together!

Is there any people whose surname are pun or poon in Henan province in china ?

Great tips! I especially agree with packing light—such a game changer. I’ve shared some destination-specific travel hacks on my own blog, mmtravelspk.com. Always fun connecting with fellow travelers!