In this extended interview, researcher Hung Ying Ying reveals her investigative process to find the ancestral village of Australian celebrity Benjamin Law and his mother Jenny Phang, as featured in the documentary series “Waltzing the Dragon” (2019). Born in Hong Kong with Fujian roots, Ying is the Research Manager at My China Roots.

Q: As a senior researcher, you have helped dozens of families trace their Chinese roots. Whose story stands out in your memory?

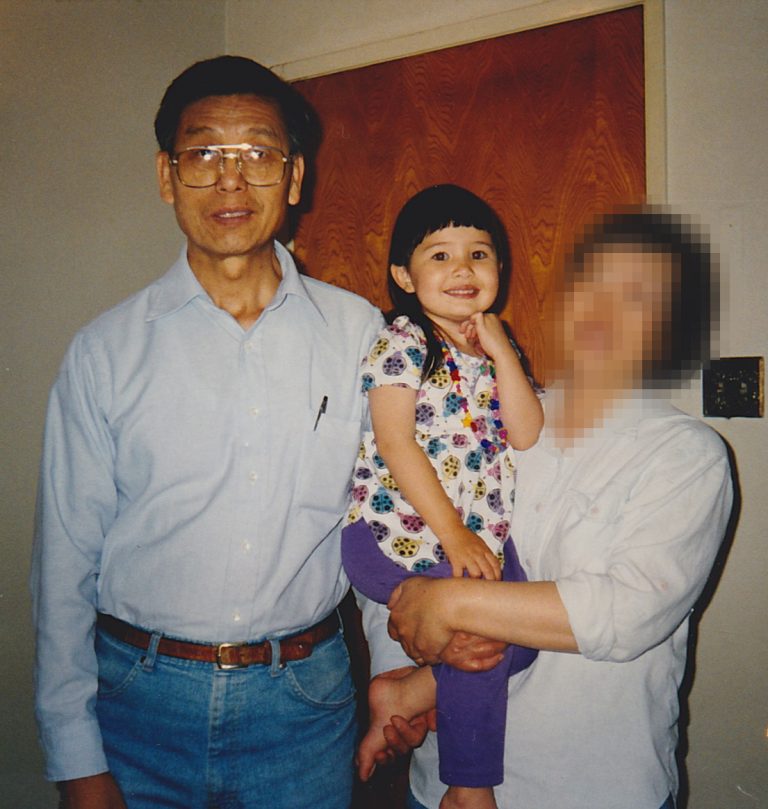

In 2019, Ben and his mother, Jenny, contacted me to trace their ancestry in Guangdong province. Ben was born and raised in Australia, while Jenny was born in Malaysia. They wanted to document the whole process with an Australian TV crew. It was my first time taking descendants with me on a live research trip!

As researchers, we spend a lot of time at the office, combing through databases, translating records, and making phone calls to all kinds of organizations. Once we’ve established promising contacts, we travel to the countryside to track down ancestral records and interview distant relatives on behalf of overseas families. I communicate with descendants all the time via email, but we don’t get many opportunities to meet face-to-face, unless they want to arrange a roots trip after the research is done.

This time, with Ben and Jenny at my side, I finally understood just how meaningful our work is. I felt a profound empathy for overseas Chinese families longing to connect to their home. Our work builds a bridge to their roots, and this impact makes me feel glad to be part of this team.

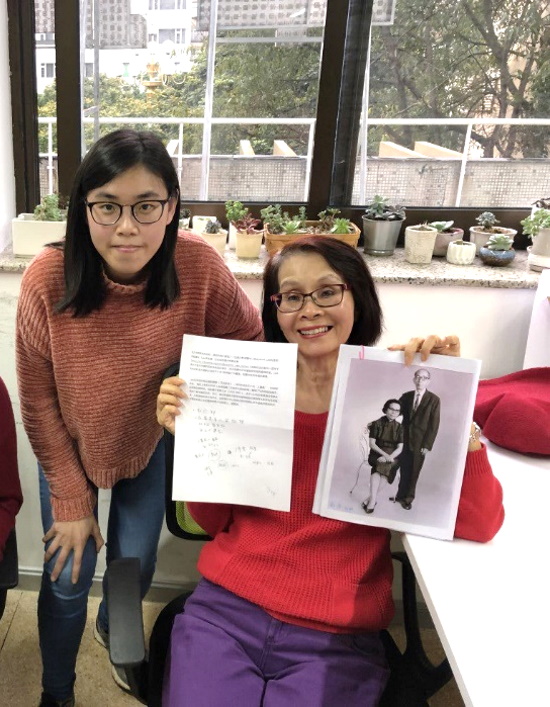

Q: Tell us about your first meeting with Ben and Jenny.

Ben and Jenny came to our office in Guangzhou on a gloomy winter morning. While tired from their long-haul flight, their eyes lit up when we started going over the research clues.

Initially, I thought this would be a typical case. Jenny speaks fluent Cantonese, reads Chinese characters, and knows quite a few stories about her family. I didn’t foresee many challenges. Then we learned that Jenny’s family had migrated several times when she was young. Few, if any, hints pointed to their ancestral village in China.

As a general rule, we need two key pieces of information to trace your Chinese ancestry: the names of your ancestors and their birthplace, both in Chinese characters.

We knew the Chinese names of Jenny’s father, her uncles, and her cousins, but their hometown was incredibly vague. All they knew was that they came from an ancient county in Guangdong province called “Upper” Panyu 上番禺 – a name which, at the time, was also used to refer to the whole city of Guangzhou. (Today, Guangzhou is home to over 13 million people.)

When I spoke of the challenges, the room went silent. I could see the disappointment on Jenny’s face. Then out of the blue, she remembered that her cousin had sent her the phone number of a possible distant relative in China, Mr Phang Shu Fai. All was not lost!

I immediately dialed the number, but my call was swiftly rejected. Ben and Jenny held their breaths as I tried again… and again… and again. It took four painful attempts before I finally heard an impatient “Hello?” ring out from my phone.

Quickly introducing myself and My China Roots, I blurted out the string of relatives Jenny knew of, hoping at least one name might ring a bell.

Suddenly, Fai interjected: “Wait a minute, I know him. He’s from my village!” It was all smooth sailing from there.

Q: How often do people refuse to speak with you during your research?

It happens at times. There are a lot of scammers, so people are bound to be suspicious. Building trust with local contacts is crucial to our work, as they provide the lifeline to records, stories, and people inside each village. It’s about finding the right balance between being respectful and being persistent until we get the answers we need.

Q: So you got in touch with Fai. What happened next?

Everything happened very quickly! Fai called me back that night to invite us all for lunch in the village the very next day. In Ben’s own words:

“Twenty-four hours ago, we didn’t know whether this was gonna be a wild goose chase among eleven million people, but now we’ve located where the ancestral village is, where the ancestral home is, and not only that, after lunch, we’re gonna go there and see it ourselves.”

We had traditional Cantonese dim sum together, but Ben and Jenny were far more interested in chatting with Fai than eating! After lunch, Fai showed us around the village as I helped translate their conversations.

Q: What do you prefer, doing hardcore research or being a roots guide?

Both require a very different mindset and experience. Genealogy research is about remaining calm, rational and disciplined. We have developed our methodology so that we know exactly what traces to look for and what to do if they aren’t traceable.

Working as a roots guide is more challenging. You need to be very flexible and quick on your feet. You cannot simply translate conversations word-for-word. You also need to convey cultural concepts implied in the conversation and advise people on how to act in a Chinese setting. Although it is hard work, it’s so rewarding to experience people’s first-hand reactions to finding their roots.

Q: What does it feel like to explore an ancestral village in person?

Ben shared how he felt walking around the village and standing in his ancestral temple:

“It is kind of mind-blowing to think that we are standing on the ground where my grandfather was just a little kid in China. I always say that if you’re the child of migrants, you cannot really fathom your parents’ experience, let alone your grandparents’ experience. It’s such an alien world. And to be here now, it’s a bit of an emotional experience.”

Even for those of us born in China, the stories of our grandparents or great-grandparents may well have been lost to time. It’s a recurring theme: when we are young, we don’t pay much attention to our elders. When we’re finally ready to start asking questions, it may already be too late. The tradition of visiting your ancestral village is still practiced by millions of mainland Chinese families each year. It is the most tangible and personal way to connect with our history.

Q: How do you “reconstruct” the life of a late ancestor? Once you’ve found their village, how do you find information about specific ancestors?

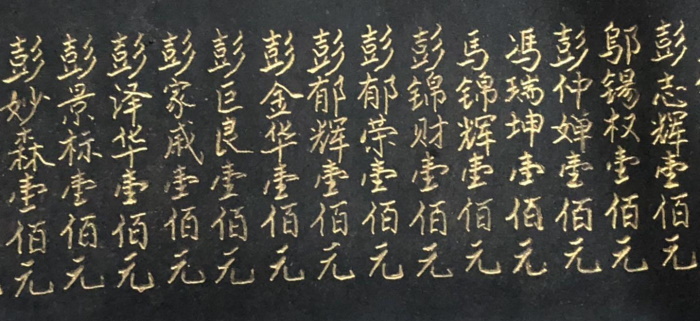

In addition to ancestral villages and houses, we typically search for records such as personal letters, old newspapers, family genealogy books (zupus), and so on. We also collect oral stories from local and elderly villagers. These puzzle pieces are our starting point for trying to find out – or otherwise, imagine – what an ancestor’s life would have been like.

In the village, I noticed a stone tablet engraved with the name of Jenny’s father. It listed all the people from the village who had contributed donations to help rebuild their ancestral hall. When I told Jenny, she carefully wiped the dust away, gently touching her father’s name. I could see her eyes brimming with tears, and again I was touched by the power of our work. This is the beauty of a roots trip: the small moments of quiet when history, stone, and skin all converge into one.

Q: How did the villagers react to Ben and Jenny’s return? How common is it for overseas Chinese to receive a warm welcome?

As we approached the village, I remember hearing the sound of stomping feet and banging drums. The moment Jenny stepped out from our car, Fai presented her with a large bouquet. A colorful parade of lion dancers proceeded to follow us throughout our tour of the village.

This cheerful procession guided us to the ancestral hall, where Fai had prepared a series of traditional rituals to honour ancestors. As villagers crowded around to talk to Jenny and Ben, I explained how they were all related to each other. It was a long day of translation, but absolutely worth it!

When darkness fell, our new friends surprised us with a grand dinner at the ancestral hall. It was an amazing family reunion, full of eating, drinking, and laughing together. Overcome with joy, Jenny shared:

“I didn’t expect this at all. It’s like more than Chinese New Year. They welcome me home because I’m my dad’s daughter…”

All in all, the roots trip was much more emotional than I expected. It felt deeply rewarding to connect Jenny, Ben and Fai. Sometimes, I wonder, “What if Jenny and Ben hadn’t contacted us? What if I hadn’t persevered in calling Fai? Would this family ever have found each other again?”

In Chinese culture, we believe that family ties are stronger than any other relationships. While not all villages may host a banquet as lavish as this, you will still be shown the utmost hospitality. No matter how far you are from home, family is family – they’ll always be here waiting for you.

Find your ancestral village and connect with Chinese relatives!

If you are interested in finding your ancestral village and connecting with relatives in China, we would love to be of assistance. Our global team of researchers has helped hundreds of families discover their Chinese roots. Learn more about our services or go ahead and get in touch!

With the global pandemic, My China Roots is offering virtual tours packaged with our research trips to your ancestral village. Check out a demo here!

Buena Historia