Growing up in the San Francisco Bay Area, Riko Yap had no doubts about his Filipino identity. After all, his family’s grocery store was the center of Filipino community life, a bustling hub for delicious meals and weekend mahjong parties.

Still, his name had always mystified him. Riko, or “rich” in Spanish (rico), made sense due to Spanish rule in the Philippines. Yet how in the world did he end up with Yap, a Chinese surname? He had no clue, other than his father’s knowledge that “grandpa’s grandpa was Chinese.”

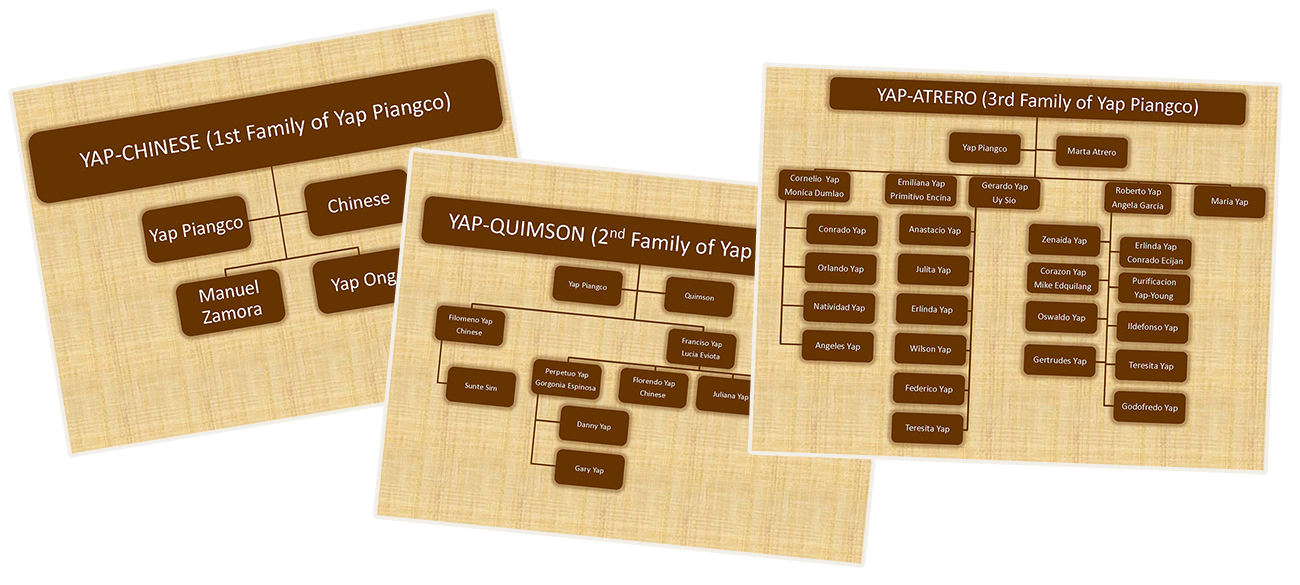

Then one night in 2012, his mother brought home a special party favor from his grand-aunt’s eightieth birthday celebration: a printout of their family tree, featuring a certain “Piangco Yap.”

“It was my first time seeing that name, even seeing our family tree go that far up,” Riko recalls. “Apparently Piangco had three wives, one Chinese and two Filipina. How were we related? What’s our connection to China?”

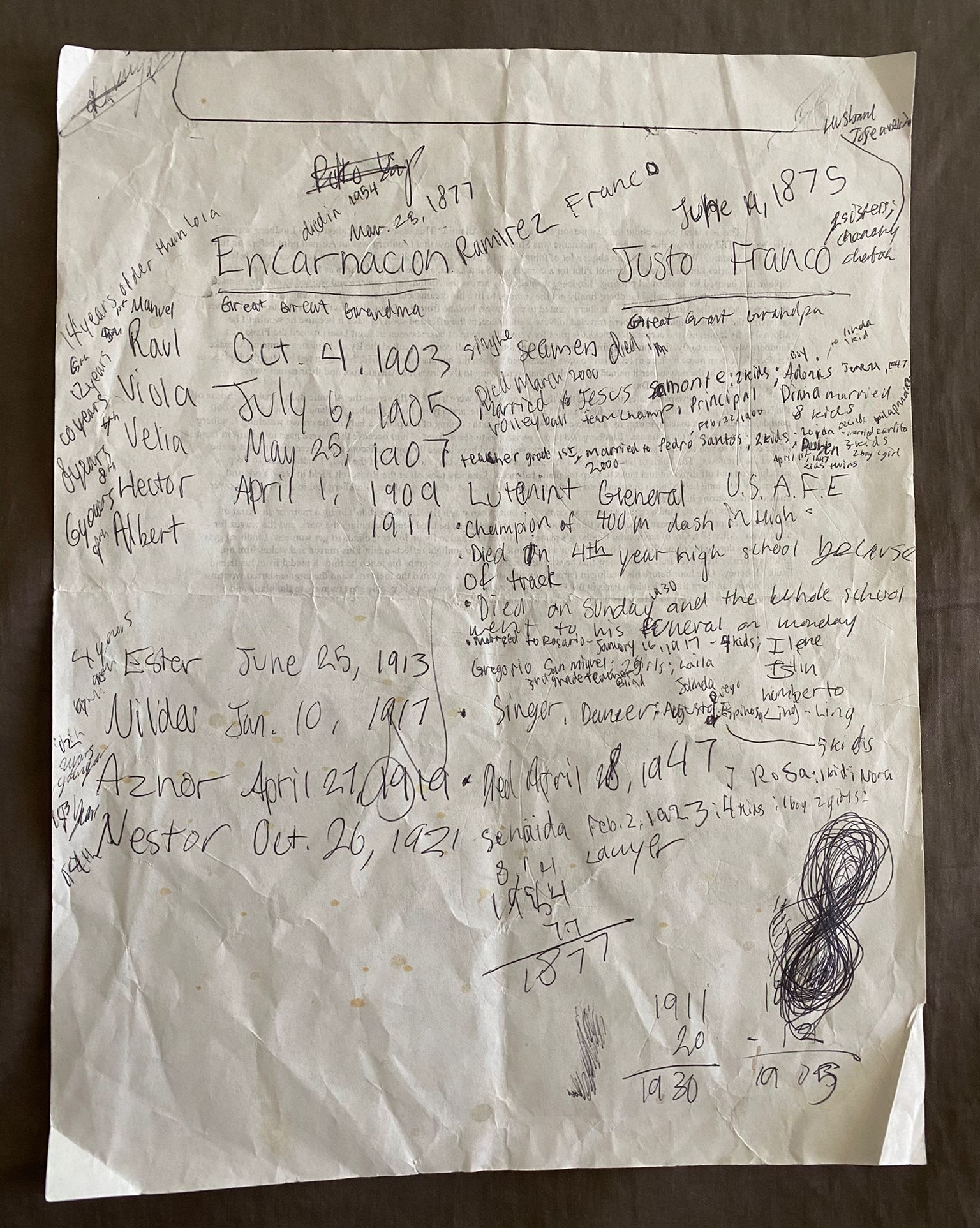

This discovery rekindled the spark of curiosity that Riko once had about genealogy as a kid. In fifth grade, he had interviewed his great-grandmother for a school project. Scribbling down names and dates, he was awed at the wealth of stories she still remembered. Seeing Piangco’s name, Riko remembered what he knew back then: “If I don’t ask, all of this will die with her.”

Reenergized, Riko swiftly took on the mantle of family historian. He mapped out eight branches on both sides of his family, compiling a family tree of over 1000 people. In the process, he reached out to any Yap he could find on Facebook, inviting them to share what they knew. Soon, Riko had gathered over 300 Yaps in a Facebook group, including relatives his family had lost touch with over time.

“It’s like a puzzle,” Riko says. “Each family has knowledge that others don’t. Our challenge is that it’s not part of Filipino culture to keep track of family history. Chinese culture has records tracking thousands of years, but most Filipinos can only go back five generations at most. We hit the point where we know we’re family, but we don’t know how.”

A breakthrough finally came in 2018 when a Yap relative posted a photo of the tombstone of Gerardo Yap, a son of Piangco and his third wife. Of all the branches, Gerardo’s family had stayed the most in touch with Chinese culture. Following tradition, his tombstone bore the Chinese characters of their Yap ancestral village: Puhou, a small hamlet in Fujian province.

Now, the search was on. With the help of the online Chinoy community, Riko soon found himself connected on WeChat with officers in the official Yap clan association in Puhou. At last, he had a direct line to find possible traces of his ancestors in China.

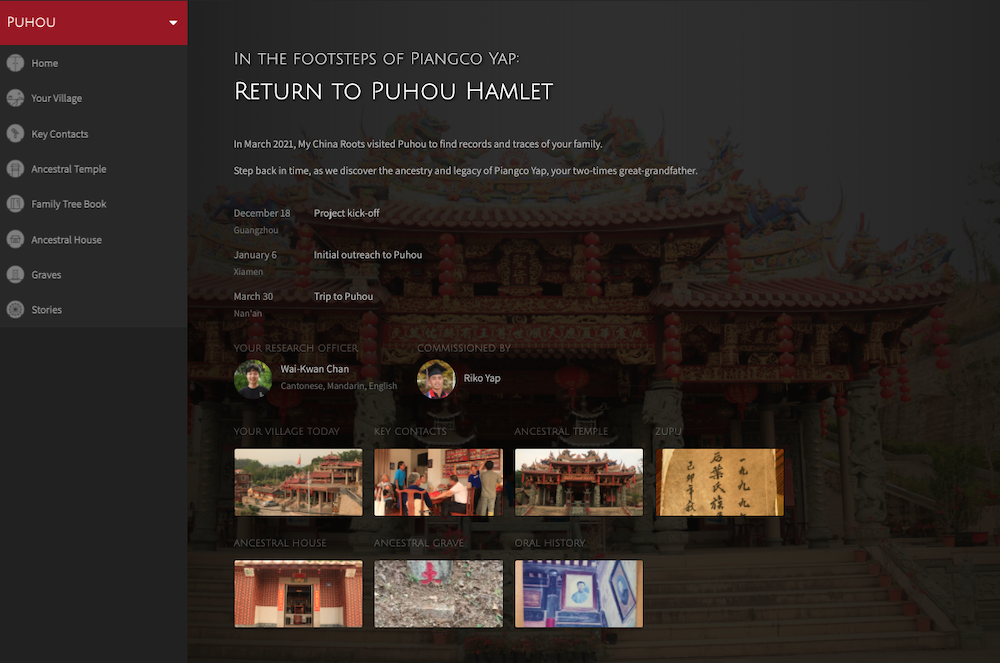

“I was so happy! But then, I had a very hard time with the language barrier,” Riko recalls. “No one spoke English, and because of the pandemic, I couldn’t just go visit. That’s when I reached out to My China Roots for help. I wanted you to go on my behalf.”

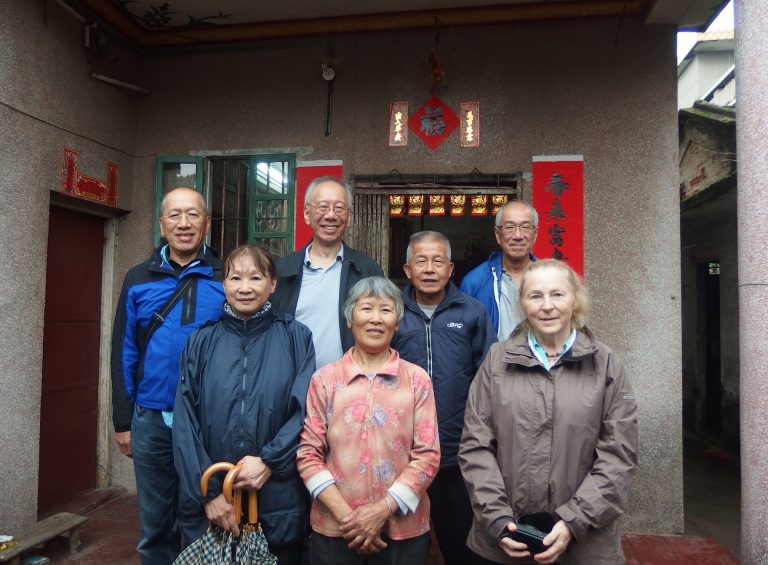

Camera in hand and Riko’s burning questions in mind, MCR researcher Chan Wai-Kwan set off for Puhou – just days before Qingming Festival, a holiday when families across China reunite to pay respects to their ancestors. Fittingly, Wai-Kwan would meet the Yap officers near the ancestral temple of Yap Sim, a heroic martyr widely revered as the common ancestor of all Hokkien Yap people.

As Wai-Kwan interviewed the officers, it quickly became clear that several were distant relatives of Riko, all descended from a family of Six Brothers. The chairman himself descended from the Eldest Brother, while Piangco (and thus Riko) descended from the Fifth Brother.

What’s more, Piangco had a brother named Footo, who also had a family in the Philippines. What Riko didn’t know was that Footo had actually left behind a family in Puhou. In fact, his great-grandson Yap Sun Kio still lived in Puhou to this day, right down the road from the temple. And he was beyond thrilled to reunite with his family overseas.

Seizing the opportunity, Wai-Kwan called Riko on FaceTime, Sun Kio beaming at his side. Despite the 15-hour time difference (and global pandemic), Riko finally found his Uncle Sun Kio alive and well in their ancestral village in China.

To Riko’s amazement, Sun Kio had never seen a photo of Footo before. Wai-Kwan pulled up Footo’s pictures from Riko – and for the first time, Sun Kio was able to lay eyes on his great-grandfather who had left China so long ago.

In gratitude, Sun Kio warmly guided Wai-Kwan to document the ancestral traces that Riko longed to see in person: their ancestral house, tablets, graves… and the Holy Grail, the Puhou Yap clan zupu (family tree book). Going back sixteen generations, the zupu confirmed that Piangco and his father were among Riko’s first ancestors to witness the fall of Imperial China and the rise of the Republic.

Upon his return from Puhou, Wai-Kwan lost no time piecing together the goldmine of findings into an interactive family website for Riko and his whole family to experience their ancestral home as vividly as possible.

“We are so pleased with the in-depth interviews and beautiful images you captured on our behalf,” Riko says. “Now, some of my relatives want to take a trip to China together. To which Sun Kio said, ‘We’re all Yaps! Just come. You are welcome here any time.’”

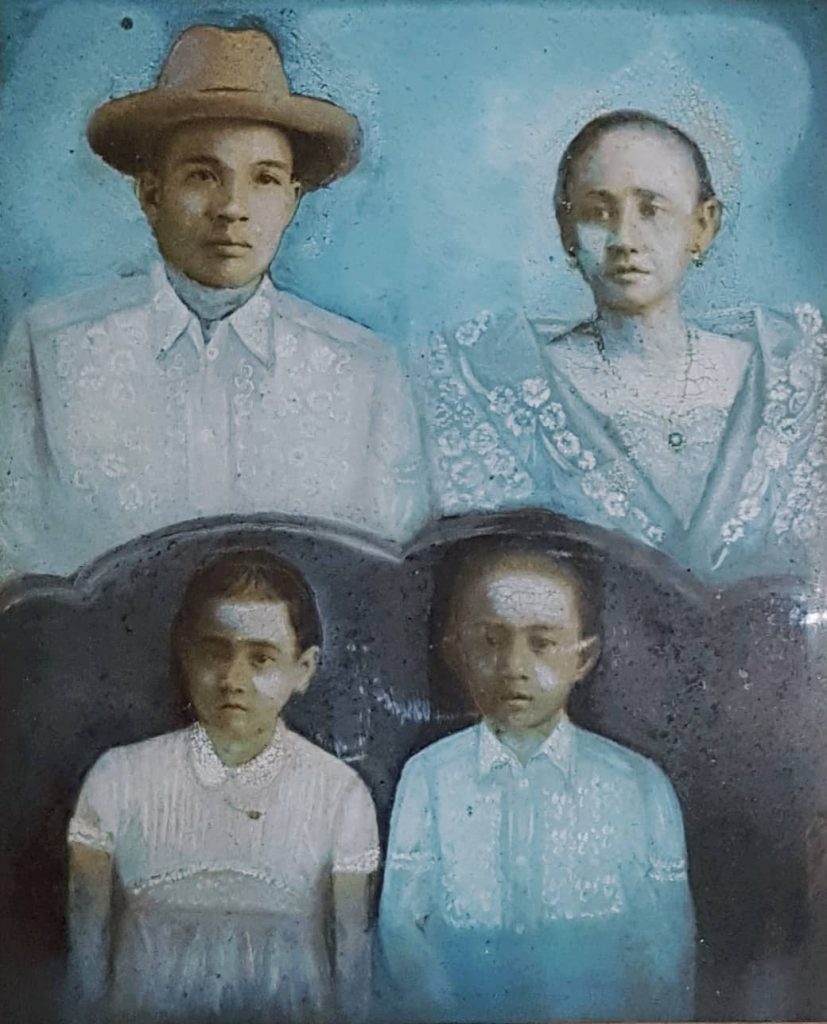

Now, Riko and Sun Kio are joining forces to unearth more genealogical gems. So far, they’ve cracked one more case: What did Piangco himself look like?

“No one seemed to have his photo, but then Sun Kio connected me with Jianhui, a great-grandson of Piangco who relocated to Quanzhou,” Riko shares. “Jianhui sent me a portrait hanging in his house, and whoa! It matched a photo I had all along from Gerardo’s great-granddaughter in the Philippines. Turns out, her father visited Quanzhou years ago. He took that picture inside Jianhui’s house!”

As for Riko’s feelings about his name these days?

“I asked Sun Kio to give me a Chinese name. He said no!” Riko laughs. “Instead, he gave me our generation poem to come up with my own name. The character for my generation is 谋, which means seek. Since Riko means rich, I chose the name 葉谋金, which means to seek wealth. Hopefully when I visit China, I can answer to my Hokkien name, Yap Bio Kim!”

Until then, Riko is making the most of his new treasure trove of records and relatives. His next mission: to trace their Yap lineage all the way back to the Yellow Emperor, the legendary father of all Chinese.

“Before, I just knew I had Chinese blood, but now I can prove it,” Riko reflects. “Start writing down your family tree while your grandparents are still alive. If you never ask, you’ll never know. I am so thankful to reconnect our long-lost roots to a rich history going back hundreds of years of Yap lineage.”

Find your ancestral village and connect with Chinese relatives!

If you are interested in finding your ancestral village and connecting with relatives in China, we would love to be of assistance. Our global team of researchers has helped hundreds of families discover their Chinese roots. Learn more about our services or go ahead and get in touch!

With the global pandemic, My China Roots is offering virtual tours packaged with our research trips to your ancestral village. Check out a demo here!

AMAZING.. I JUST STARTED SEARCHING MY GRANDFATHERS ROOTS IN CHINA.. COULD BE FUJIAN WHERE MOST YAP LEFT and MIGRATED TO PHILS.. ACDG TO MY MOM, HIS PAPA N RELATIVES SCATTERED IN CEBU. LEYTE.. MY G’PA OWNED GROCERY STORE IN ALBUERA LEYTE around year 1900

My great grandfather was a Yap and lived in Cebu before moving to Mindanao. Heard stories about they own multiple businesses including buses but failed to sustain it. All I know is his name is Chiong