I grew up hearing stories of my people, the Hakka, and how we are the descendants of refugees escaping war and turmoil in northern China.

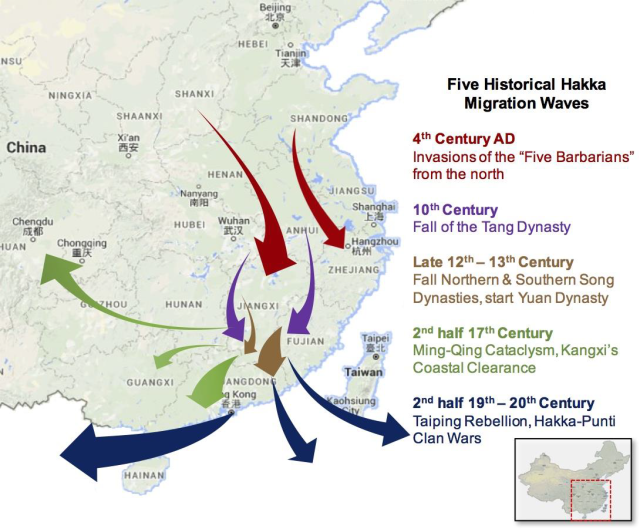

According to legend, we migrated from the Central Plains to the south in five, epic waves, eventually settling in an area straddling modern-day Guangdong, Fujian, and Jiangxi provinces. Our ancestors had no choice but to flee their homeland and become guests in the lands of others; while still clutching dearly to our birth right as heirs to Chinese civilisation. That, I was told, is why we are called kejia 客家or “Guest Families”. I loved hearing this story.

But as I grew older, it dawned on me that things didn’t quite add up. Other Chinese “dialect” groups, such as the Cantonese, Hokkiens, Teochews, also originated in the north.

So why were the Hakkas the only ones considered ‘guests’?

A Not-So-Special Origin Story

I carried this dubiety for a long time. Eventually, procrastination at university led me to make a startling discovery: the five migration waves were not so unique to the Hakkas after all.

For example, the ancestors of the Min people (which includes Hokkiens, Henghuas, Hockchews, etc) also moved southwards in great numbers around 300 A.D., during the northern invasion of the Five Barbarians (五胡乱华). This event corresponds to the first of the Five Great Migrations of the Hakkas, and in the Min context, it’s known as the Eight Clans Entering Fujian (八姓入闽).

In ‘New Theories on the Origin and Development of the Hakkas’, Chen Zhiping studied genealogical zupu records for over 50 clans. Almost every zupu he consulted, Hakka or not, made reference to a southern migration from a northern origin.

By painstakingly tracing the genealogy of southern Chinese clans, Chen found that not only do Hakkas and non-Hakkas have common ancestors, but that mutual migration between Hakkas and non-Hakkas also meant that individual families coalesced into others. Thus, a Hokkien person could migrate to a Hakka region, learn Hakka, and down the line his descendants would become Hakka themselves, or vice versa.

Reading all of this, I knew I was right to doubt the uniqueness of the Hakka’s migratory history. After all, all southern Chinese had come from the north. However, this still didn’t answer my second question.

Out of all these distinct groups, why were only the Hakkas considered guests?

Speaking “Our” Language

But before I get to that, I would like to recount my personal roots trip in 2019 to Heshui town, Xinyi, Guangdong (信宜市合水镇). Xinyi is located in the west of Guangdong, close to the border with Guangxi. Upon arrival in Guangzhou, a relative (who also happened to be the head of the clan association) picked me and my travel buddy up and drove us to Xinyi. I had learnt from my research before the trip that in western Guangdong, the Hakka language has a few names: Ngai, Xinmin (新民话) and Magai (麼个话). Unsurprisingly, most of my Heshui relatives didn’t refer to themselves as Hakka. Whenever they mentioned their language, they would say “gong Ngai” (讲𠊎). Ngai being the first-person pronoun in Hakka, meaning “I/me”. Hence, the Ngai language just means “my/our language”

I recall one instance where one cousin in his 50s told me about the name of the family cemetery location. Because we conversed in Mandarin (as we had quite different accents speaking Hakka), I asked:

“How do you say it in Hakka?”

He paused for a while, before asking back “you mean in Ngai?”

“Yeah in Ngai”, I replied.

I later overheard other relatives commenting about how I spoke Hakka. This meant two things: firstly, they knew what Hakka was, and secondly, they don’t consider their language to be Hakka.

Later on, the same cousin told me that what they speak is a variety of Hakka. He was probably trying to save face on my behalf. We soon left Xinyi and drove to Foshan, where many of them now live and work. I met another relative who, despite being in his thirties and me in my twenties, would be considered my nephew. I remember noting that although he had that twangy Ngai accent when he spoke to his father, he spoke to me in a much more understandable accent, and he took no issue with the term Hakka. Having spent his teen years studying in Guangzhou, I wondered if he met other fellow Hakkas at that time which impacted his feelings around the term.

“Guests” in a Foreign Land

Meeting my relatives made me wonder why people who clearly speak Hakka didn’t identify as such. When exactly did we start calling Hakkas Hakka?

The term first appears during the Ming and Qing dynasties, when conflict between Hakka migrants from Jiaying Prefecture 嘉应州 (today known as Meizhou 梅州) and natives are well documented in the gazettes of several cities with mixed Hakka populations. Many migrants registered as ‘foreign households’ (客籍/客户) to receive state incentives. At this time, the word for ‘guest’ 客 here did not yet refer to a Hakka ethnicity, but simply meant people not living in their registered hometowns.

As more Jiaying migrants settled and competed with resources with the natives who spoke a different language, conflict was inevitable. The most notable conflict was the Punti-Hakka clan wars of 1856-1867, which happened in the south west corner of the Pearl River Delta, also known as the Seiyap (四邑) region. The scale of the conflict was particularly large as it occurred during the Taiping rebellion, when the Qing authorities had no control over the south. Over the 12 years, casualties among both the Hakkas and the native Cantonese reached 500-600 thousand.

Thus, the term Hakka only appeared in the specific conflict between Hakkas and Cantonese. As early as 1815, a paper written by the then dean of the Fenghu Academy in Huizhou (丰湖杂记) noted that the native Cantonese called the foreign settlers 客, a term also used by the settlers themselves. This paper is considered to be the earliest written testament of a distinct Hakka identity vis-a-vis the Cantonese.

Defining Hakka-ness

While the conflict between Hakkas and the Cantonese had been long ended by the 20th century, the animosity between them did not. In 1905, Huang Jie, an ethnically Cantonese historian, published a book that claimed that the Hakkas “are neither Cantonese nor Han” (非粤种亦非汉种). This triggered a backlash from Hakka intellectuals in an ensuing war of words. 15 years later in 1920, a geography book published by the Commercial Press in Shanghai referred to a “backwards population” living in Guangdong, which started another backlash culminating in the founding of the Tsung Tsin Association (崇正总会) in 1921. Founded by Hong Kong University-educated Hakka professor Lai Jixi (赖际熙) from Hong Kong University, it sought to dispel myths and misunderstandings about the Hakka people.

The final piece consolidating the image of the Hakka we often see today, was the publishing of Luo Xianglin’s 1933 book, Introduction to Hakka Studies (客家研究导论). This was where the familiar Five Great Migrations theory came in. In fact, after Luo’s theory was taken as gospel within Hakka circles, many scholars who visited Hakka speaking populations outside the Hakka heartland of Fujian, Guangdong and Jiangxi were surprised to find that these populations in Sichuan and western Guangdong (where my Ngai relatives live) for example, don’t call themselves Hakka. But the scholars preached the Hakka identity to them regardless.

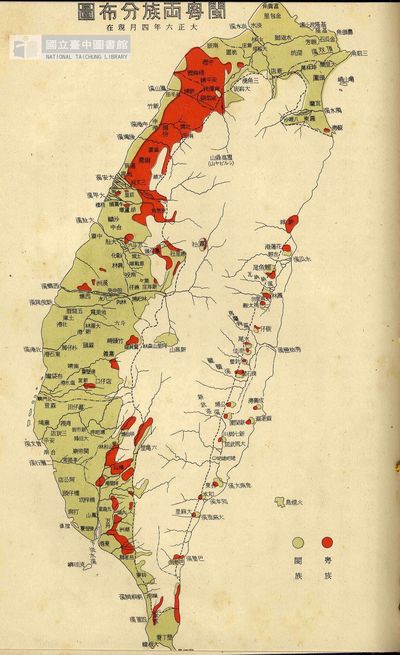

In fact, Hakka speakers in Taiwan did not call themselves Hakka until 1945, with the retrocession of the island to the Republic of China. In Sichuan, where Hakkas have lived since the early 1700s, the term was only adopted in the 1980s after the opening up and reform period. In both places, the Hakkas were previously known as people from Guangdong, 广东人.

Conclusion

No doubt, the story of the Five Great Migrations is attractive. It certainly helps that the Hakkas are stereotyped to be patriotic (such as during the Hakka uprising against the Japanese when they took over Taiwan in 1895), and outstanding in politics and military affairs (Lee Kuan Yew, Deng Xiaoping, Tsai Ing-Wen, Ye Jianying, and more dubiously, Sun Yat Sen). Our shared history of displacement was supposedly what imbued in us a greater sense of community.

Although new information about Hakka history has been published in the last 20 years, the Five Great Migrations theory stubbornly persists. It does make for great storytelling, and gives us a shared sense of history and identity.

However, it is ironic that as a response to being othered, we adopted a name that connotes foreignness.

We call ourselves the Guest People, and in doing so, we have perpetually othered ourselves.

Further Reading:

客家:误会的历史、历史的误会 by 刘镇发 (Hakka: Misunderstood History, Historical Misunderstandings by Lau Chun Fat.

Migration and Ethnicity in Chinese History: Hakkas, Pengmin, and Their Neighbors by Leong Sow-Theng

客家源流新论 by 陈支平 (New Theories on the Origin and Development of the Hakkas by Chen Zhiping).

Find your ancestral village and connect with Chinese relatives!

If you are interested in finding your ancestral village and connecting with relatives in China, we would love to be of assistance. Our global team of researchers has helped hundreds of families discover their Chinese roots. Learn more about our services or go ahead and get in touch!

With the global pandemic, My China Roots is offering virtual tours packaged with our research trips to your ancestral village. Check out a demo here!

Funny that you say that your relatives don’t consider what they say is Hakka but, Ngai. My mom’s entire family and relatives are Ngai but, from Vietnam. They been there for a few generations and came to the U.S. after the Vietnam War. My dad’s side is from Guangxi and I’ve been there before. There are Ngai speakers in Guangxi too because my mom was speaking to them in Ngai. Wonder what it is about it because my mom said she can “understand” Hakka as if Ngai is something separate. But there’s not just one Hakka language but, Hakka is probably a term that’s used by others to describe that group? It’s sort of a mystery to me. 😆

Your blog never ceases to amaze me, it is very well written and organized.*-.:;