One year on a visit back to Yunnan, my family took a day trip to Kunming’s Stone Forest. As we walked among the spectacular stone formations of elephants and “eternal mushrooms,” a white butterfly danced around our heads. It followed us for a while, and my cousin Tairan said, “It must be Yeye, welcoming you home.”

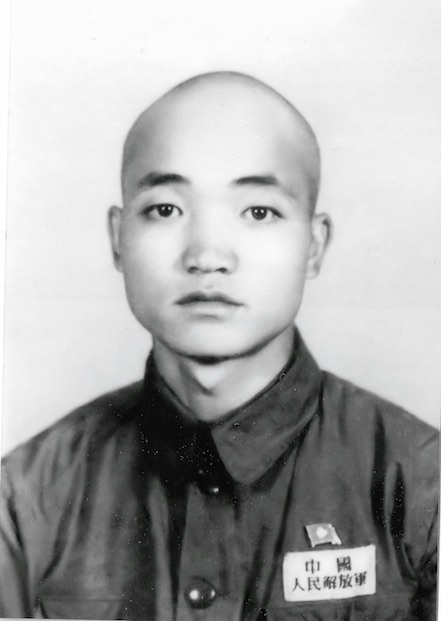

I only met my paternal grandfather once, when I was three. It was the first time I went “home” to Lincang, and I don’t remember it. Lincang was always home to Yeye, where he married and met my Nainai in 1956. They raised four children together, my dad being the eldest. After he passed away, Yeye’s presence has always been felt, his beaming smile watching over us from the altar at Nainai’s house.

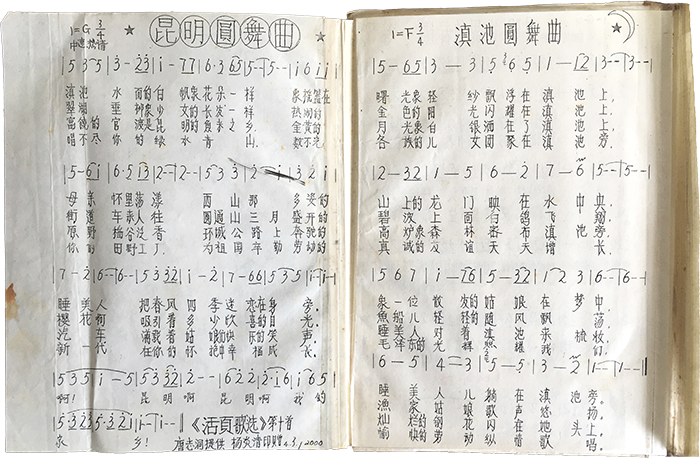

In most photos I’ve seen of him, Yeye is holding either his erhu or tobacco pipe (or both). As the musicians of the family, my brothers and I inherited his erhu and book of musical scores, a mix of revolutionary tunes and Yunnan indigenous folk songs.

I was always intrigued, but I didn’t learn to play the songs until a decade or so later, when I joined a Chinese music ensemble in university. I didn’t get very good at the erhu, but it feels pretty cool knowing that my fingers are winding their way around the same melodies he once played. From 紫竹调 (“Purple Bamboo”) to 云南美 (“Beautiful Yunnan”), I walk down the street, the same tunes stuck in my head, wondering:

When did he learn these songs? Why did they resonate with him? Behind that beaming smile, what was life truly like for my grandfather?

Revolutionary Self-Criticism: The Official Story

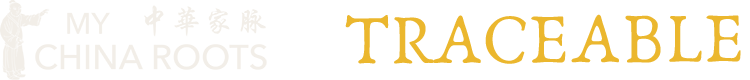

Not long ago, I discovered some of Yeye’s writings in a box that my dad had kept in the attic for years. What I found complicated how connected I feel to recent Chinese history.

Written in 1975, most of his recollections take the form of a self criticism (自我批评). Self-criticisms were an essential part of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s efforts to draw out and eliminate enemies. Those accused or suspected of counterrevolutionary thoughts or behaviours were forced to undergo “political rehabilitation” and write self-criticisms outlining their mistakes, as evidence of their counterrevolutionary ways.1As Mao stated in 1945:

Conscientious practice of self-criticism is still another hallmark distinguishing our Party from all other political parties. As we say, dust will accumulate if a room is not cleaned regularly, our faces will get dirty if they are not washed regularly. Our comrades’ minds and our Party’s work may also collect dust, and also need sweeping and washing […] To check up regularly on our work and in the process develop a democratic style of work, to fear neither criticism nor self-criticism, and to apply such good popular Chinese maxims as “Say all you know and say it without reserve”, “Blame not the speaker but be warned by his words” and “Correct mistakes if you have committed them and guard against them if you have not” – this is the only effective way to prevent all kinds of political dust and germs from contaminating the minds of our comrades and the body of our Party.”

On Coalition Government” (April 24, 1945), Selected Works, Vol. III, pp. 316-17.

Interspersed with quotes from Mao Zedong and letters exchanged with the CCP committee of his work unit, Yeye’s self-criticism explains the story behind the accusations made against him for being counterrevolutionary: getting caught up with the wrong crowd as a 21-year-old in 1949, a period of political turmoil and intense violence in the borderlands of Yunnan and Burma. He writes:

“I was born and raised in a poor family. Before liberation,2Liberation happened in 1949 in most of China, but as the PLA took longer to reach remote regions like Lincang, it wasn’t officially liberated until 1950. I lived a painful life of desperate poverty, without a job or a home. In June 1949, I joined the 9th Detachment of the Borderland Guerilla Military Unit, under the leadership of our great Party. […] During the Gengma battle, our military unit made a rapid day-long retreat back to Ganhaizi in Shuangjiang.

Also under the united command of the guerillas, bandit Yang retreated with us from Gengma to Ganhaizi. Because I hadn’t been through formal training, I lacked vigilance. I fell asleep at the foot of a wall, waking up around ten minutes later with unit leader Qiu standing beside me. I suddenly realised that bandit Yang had taken advantage of my slumber and stolen the small pistol and leather purse containing forty yuan that I usually wore on my person.

After my gun was stolen, I should have continued moving with the guerillas. But because my thoughts were in a muddle, and because I feared being subject to punishment, I left them and wandered around destitute in Shuangjiang. Here I began to follow Pengsi3A famous bandit and Communist defector in Lincang. and local bandits Dibawuzhuang and Ye Jiabao, who at the time were under the guerrilla band’s united leadership. I joined them for around half a month, but I didn’t do anything bad. After going with them from Shuangjiang back to Lincang, I chose to leave him and return home.”

Part of me desperately wants to read Yeye’s writings as a window into who he was. After all, little is written about the borderlands outside Beijing, like Yunnan, during this chaotic period of Chinese history. During my university studies, I rarely came across stories from the perspective of everyday people. Most historical accounts are de-personalized, centering the memories and writings of those in power.

But it’s a self-criticism. I have to take it with a grain of salt. He wasn’t writing a diary. He was writing for his own self-preservation. In between the lines, I can hear how he has emotionally distanced himself in order to prove his innocence. Unlike his expressive notes on the erhu, here he writes matter-of-factly, without feeling.

For instance, is his confessed “lack” of “formal training” and “vigilance” really to blame for why he fell asleep on duty? I looked up the distance his guerrilla unit crossed from Gengma to Ganhaizi: roughly 1200 km or 745 miles, the equivalent of 20 hours by car. I don’t know about you, but I’d need a nap after trekking for weeks on foot in the middle of a civil war.

Reading the trauma he experienced, I’m amazed at how resilient he was, to be swept up in the chaos and survive it. Although the pressure to be on the “good” side of history has distorted his side of the story, it’s remarkable that he lived to tell this tale — and that I exist to tell it, too.

Tales by the Scottish Sea: The Real Story

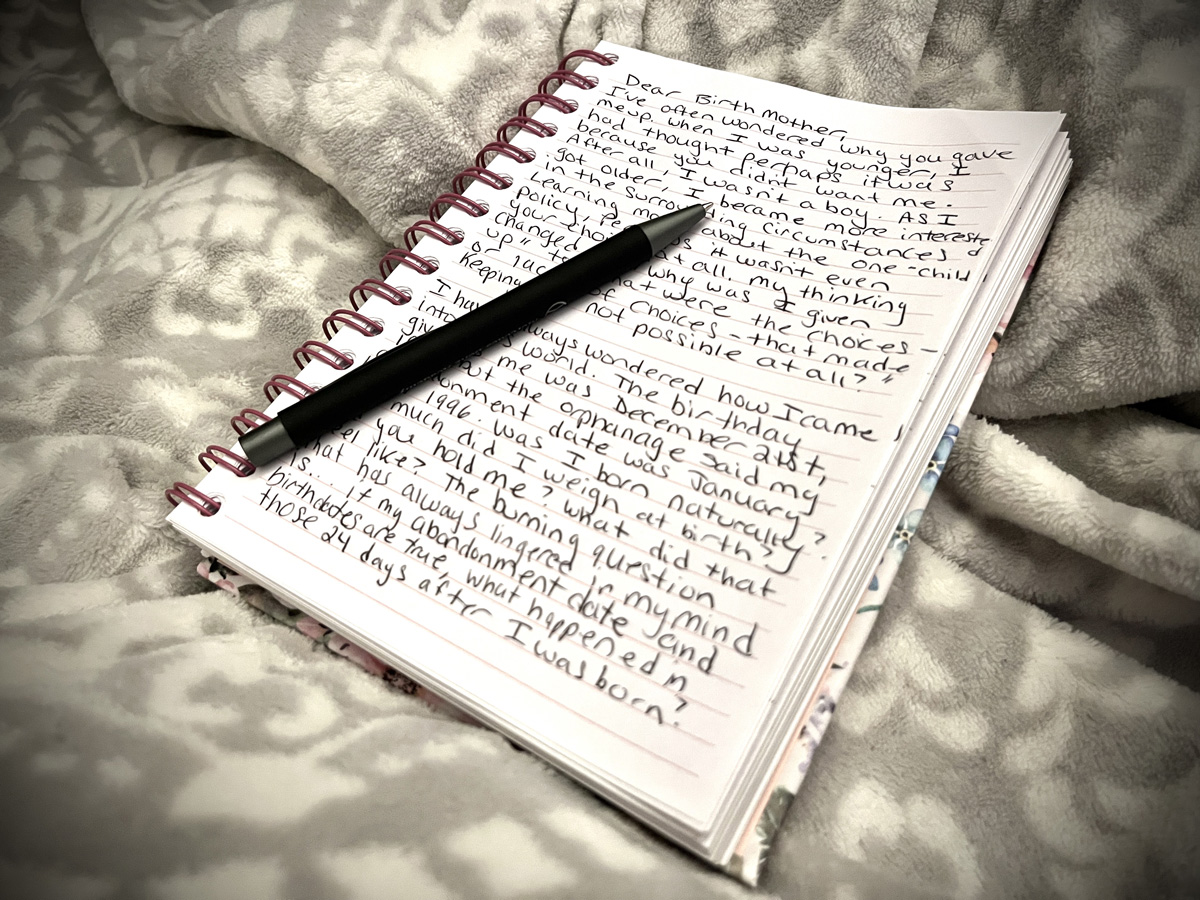

In 1992, Yeye left China for the first time in his life to visit my parents in the United Kingdom. My maternal grandfather loves retelling the story of Yeye’s visit to his home in Conicavel, a remote village in the north of Scotland:

“Every morning he got up before breakfast and walked up and down the village street in his hexagonal hat and high collar. He peered into people’s windows and gardens, he smiled at everyone and everyone smiled back. He got a great reception!

There was a language barrier because his only English words were hello, goodbye, and whiskey, as far as I remember. But we knew he loved music, so we asked all the musicians we knew to come for a party in our cottage in Conicavel. So we had your granddad singing Chinese opera, your dad singing revolutionary songs, your uncles playing some country and western, a friend playing Shetland fiddle tunes, and another pal, a piper, playing the bagpipes. People were dancing and leaping around. There was a lot of drink being drunk.”

Compared to Yeye’s self-criticism, it’s these stories from my Scottish family that make me feel closer to knowing him. Whenever they talk about him, it’s like they’re in awe of him. My uncle Tom (who inherited Yeye’s tobacco pipe) shared this larger-than-life memory:

“In the morning I thought I’d see if the old fella wanted a cup of tea or anything. I tapped on his door, but there was no answer. He wasn’t there. … Amazingly he’d gone out, when it was still dark on a stormy November morning, and walked maybe half a mile to a mile down a single track road to the pier to do his taichi in the morning, being sprayed with saltwater and these big waves slapping against the pier…”

Yeye’s presence clearly put people at ease. He was comfortable in his own skin, and those around him felt it too. In my uncle’s words, it was remarkable “how straight-forward it was, that [we] had this cool easy relationship with this old guy from China. There wasn’t much of a boundary. We made it work!”

Music in the Park: My Story

One particularly hot afternoon last summer, my Nainai took me to a park in Lincang. As we approached a colourful pagoda surrounded by trees, music began to fill the air.

With one hand, Nainai squeezed my arm: “This is where your Yeye used to play.” Her other hand pointed to a congregation of elderly musicians reclining under the pagoda, flasks of tea at their feet, playing with leisure and contentment. In the neighboring shade, more elders sat on short stools, smoking or gossiping with each other. Every so often, people stopped to watch and listen, before continuing their meander through the park.

Nainai and I make ourselves comfortable. With my hands in hers, I close my eyes and let the familiar melodies wash over me, undulating in the sunlight.

As I soak in the weaving strains of folk music, a white butterfly appears before me. For a moment, it flutters above the musicians’ heads, before gently flitting away again.

Find your ancestral village and connect with Chinese relatives!

If you are interested in finding your ancestral village and connecting with relatives in China, we would love to be of assistance. Our global team of researchers has helped hundreds of families discover their Chinese roots. Learn more about our services or go ahead and get in touch!

With the global pandemic, My China Roots is offering virtual tours packaged with our research trips to your ancestral village. Check out a demo here!