Life in the past wasn’t easy. This is a reality that we genealogists are faced with on an almost daily basis. Invariably, a key component of the inspiring personal stories we unearth is adversity and struggle.

For those with Chinese heritage, this was especially true for their migrating ancestors. A Chinese gentleman seeking to migrate at the turn of the 20th century, for instance, could add a further difficulty to his list of woes: exclusion. At the end of a 4000-mile journey from southern China to the United States, or Canada, or Mexico, or any number of other countries, he would come up against a mess of racist exclusionary policies targeted against him, a man of Asian heritage.

In this blog post we unpack some of the discriminatory migration policies your Chinese ancestors might have had to overcome.

1. Australia

In the early 20th century, Australia was undergoing a gold mining boom, fueled by plentiful low-cost labour. Local, white, labourers, however, were unhappy with the competition posed by immigrants from Asia and the Pacific Islands, who came to the island to partake in the gold rush.

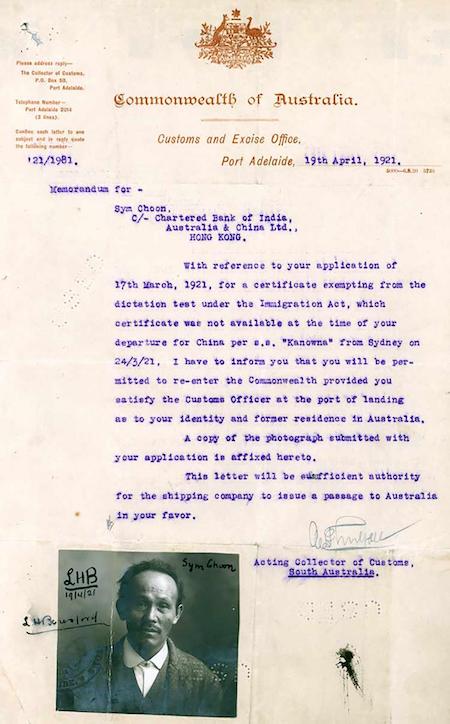

The colonial government in Australia had already begun imposing restrictions on Chinese immigrants in the latter half of the 19th century, prohibiting families from coming to the island to join their labourer relatives. Then, in 1901, the country passed the Immigration Restriction Act, which demanded that all incoming immigrants must be able to “write out a dictation and sign… a passage of fifty words in length in an European language”. This dictation test effectively excluded Chinese immigrants. What’s more, it began what came to be known as the “White Australia Policy”, a series of policies aimed at limiting migration to the country to European countries, particularly Britain. These policies persisted right up through the second world war, with wartime Prime Minister John Curtin saying: “This country shall remain forever the home of the descendants of those people who came here in peace in order to establish in the South Seas an outpost of the British race.”

The policies were dismantled in stages after the conclusion of World War two, culminating in the Racial Discrimination Act of 1975, which outlawed racially-based selection criteria for incoming immigrants.

As with other discriminatory policies, one silver lining for us genealogists is that they create a paper trail, which can provide crucial insights into our ancestors’ stories. A good example is the Chinese Register of Exemption from Dictation, a volunteer-led project that documents a list of names and personal details of Chinese residents of the Australian of Victoria, who were exempt from sitting the dictation test when they returned from overseas trips.

2. United States

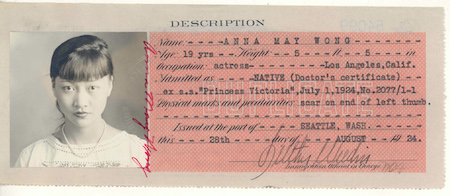

The most notorious piece of anti-Chinese migration policy in the U.S. was the Chinese Exclusion Act, passed as early as 1882. The law, which banned all ethnic Chinese migration to the country (with very limited exemptions), remains the only piece of U.S. legislation to ban all members of a specific ethnic group from entering the country.

As was the case in Australia and Canada, the law was prompted by local concerns over competition from an influx of Chinese labour. Where Chinese people had been instrumental in the Australian gold rush, Chinese Americans were crucial in the construction of the country’s railroads. President Chester A. Arthur passed the law after a series of race riots and anti-Asian violence. The law is particularly salient for being passed in the late 19th century, when the U.S. was ostensibly still operating an “open door” migration policy, making it one of the only anti-immigrant policies in all of North America at the time.

It was replaced by the Magnuson Act in 1943, which allowed a small quota of 105 Chinese immigrants a year, and later by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which did away with the quota-based system of migration entirely.

One notable legacy was the creation of what has come to be known as “paper sons”. With increasingly restrictive policies targeting them, Chinese immigrants took to purchasing false documents claiming that they were related, usually as a son or a daughter, to Chinese Americans who had already obtained U.S. citizenship. This was particularly prevalent after the San Francisco Earthquake of 1906 destroyed the city’s public records office. Chinese Americans in the city could then claim that they had always been U.S. citizens. They could do the same for people back in China by claiming (often falsely) that they were their sons or daughters.

To counter this, Chinese immigrants were subject to strict and arduous interrogations about their purported heritage and background on arrival in the U.S. The resulting interview transcripts can be found at the National Archives Catalog, and are an invaluable resource when it comes to learning about your Chinese American ancestry.

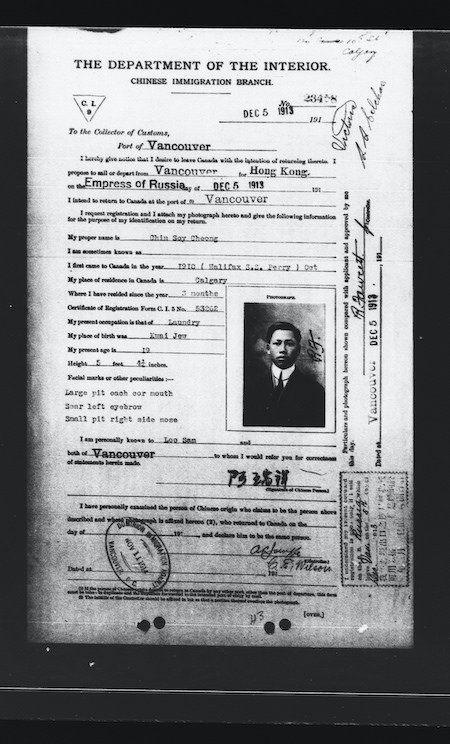

3. Canada

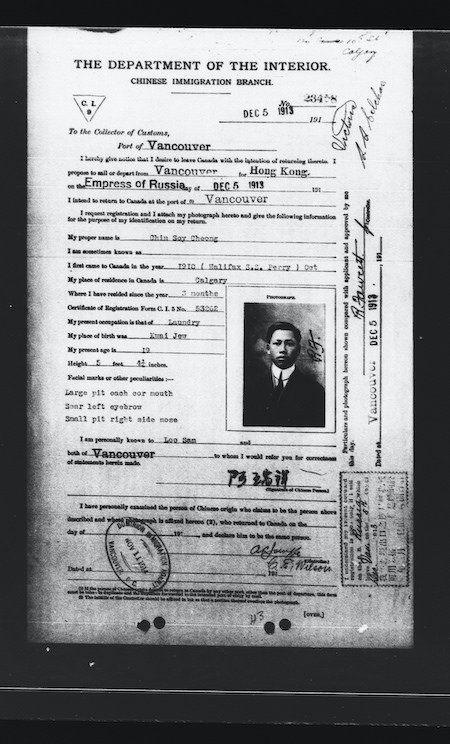

The situation in Canada was similar to that in the U.S. After the passage of the Chinese Immigration Act of 1885 (passed after tensions in British Columbia about Chinese railway workers), all Chinese immigrants to Canada were forced to pay an onerous 50 CA$ fee on entry. This was increased several times before reaching its maximum of 500 CA$ in 1903. According to the Canadian Research and Knowledge Network, wages for Chinese workers on Canadian railways could be as low as 1 CA$ per day.

The act was later replaced by the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, which all but prohibited any ethnic Chinese person from migrating to the country. The act lasted until 1947, when it was disbanded for coming into conflict with Canada’s signing of the United Nations Charter of Human Rights. However, race-based exclusion policies were not done away with until the 1960s.

Most of Canada’s head tax records are searchable via the Canadian Government’s Database of Chinese Immigrants (1885 – 1949).

4. Jamaica

Chinese migration to Jamaica began in the late 19th century, when thousands of indentured labourers were brought over to replace African American slaves on the island’s plantations. By the early 20th century, however, independent Chinese immigrants began to outnumber their indentured countrymen and a 30 pound tax was levied on each Chinese arrival. They were also subject to a written test to prove they could write a short passage in at least three different languages. The restrictions were tightened in 1931 and again in 1940, when arrivals from China were limited only to students and diplomats. They were later relaxed slightly in 1947 after pressure from the Chinese consulate led the government to allow a limited quota of Chinese immigrants.

5. Mexico

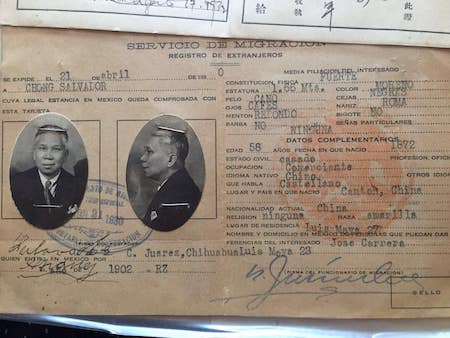

Chinese Mexicans have a long and storied history. The earliest mass migration began in the 1870s as the country sought to entice immigrants to populate its arid northern deserts. It picked up in the late 19th century as many Chinese Americans fled the increasingly hostile situation in the U.S. With the formal establishment of diplomatic relations between Mexico and Imperial China in 1899, Chinese immigrants to Mexico officially enjoyed the same rights as Mexican Citizens. In the following decades, the population boomed, reaching over 25,000 in the mid 1920s. By this time, Chinese Mexicans, many of whom had arrived in the country as manual labourers, had become well represented in the country’s industry and business circles.

The success of Chinese-Mexicans, however, bred resentment from the local population, particularly in areas like Mexicali and Sonora, where Chinese Mexicans had come to dominate the merchant and business classes. Tensions boiled over in the Torreón Massacre of 1911, in which over 300 Asian Mexicans, largely Chinese immigrants from Guangdong were killed, and their homes and businesses destroyed. Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador apologized for the massacre in May 2021, underlining “The Mexican state will not allow, ever again, racism, discrimination, and xenophobia.”

Tensions continued to rise as Mexico’s economic fortunes declined. In the wake of the Great Depression, economic envy of Chinese Mexicans was so great that the government began mass deportations of Chinese across the country. By some estimates, some 70% of the Chinese and Chinese-Mexican population were forcibly deported during the 1930s.

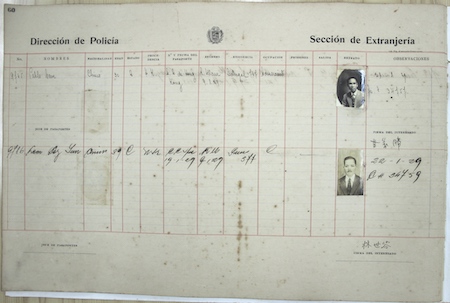

The National Archives of Mexico (in Spanish) have indexed Chinese arrivals to the country in the 20th century.

6. Peru

By some estimates, as much as 15% of the population of Peru has some sort of Chinese heritage. They are the descendants of indentured labourers brought to the country in the late 19th century, often to work in the country’s unforgiving guano mines.

By the early 20th century a Chinese community of several thousand residents had established itself in Lima. In 1909, a series of riots occurred where the local population sacked the city’s Chinese quarter and demanded that the government limit the flow of Chinese immigrants to the city. The government relented and signed the Porras-Wu Tingfang protocol, which limited Chinese immigrants to the country that year. After World War Two, the government brought in further restrictions on immigrants, including Chinese. Not only did this stem the flow of arrivals, but it also accelerated the process of localisation of immigrants already in the country, with many Chinese Peruvians adopting hispanic names and religions.

The government also agreed to keep a record of all arrivals from China. These records can be viewed in person at the Archivo General de la Nación in Lima. By one of our Peruvian researchers’ estimates, there are 23 books of 400 pages each recording Chinese arrivals in the archives, containing some 37,000 names!

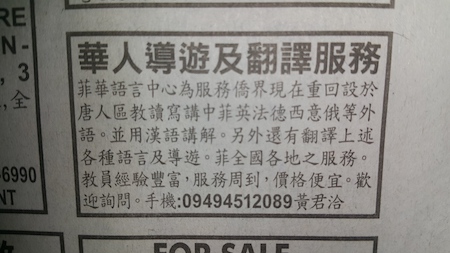

7. Philippines

The Philippines has one of the largest populations of ethnic Chinese people in all of southeast Asia. Nonetheless, there was a time when arrivals from China were all but barred. When the country was still a U.S. colony, the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 applied in the Philippines also. However, as was the case across the Pacific, Chinese immigrants were able to circumvent the law by changing their identities or being adopted into local Chinese Pilipino families.

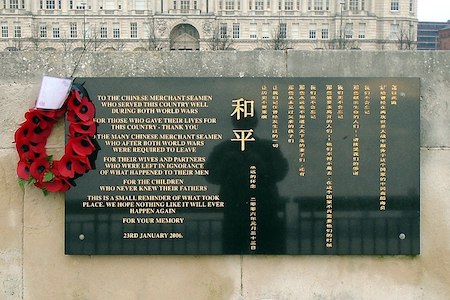

8. United Kingdom

In the 19th and early 20th century many Chinese immigrants in Britain were sailors. Ports like Liverpool and Limehouse in London had substantial populations. Many of these sailors served and died on merchant ships during the two world wars.

A wave of anti-Chinese feeling swept Britain at the turn of the century, with the country’s Chinatowns – particularly at the docks in Limehouse – wrongly seen as dens of vice and iniquity. Tensions also ensued over competition for jobs, with the British Chinese seaman a source of cheap labour for Britain’s empire. After riots in 1904 and 1905, anti-Chinese feeling became a key issue in the country’s 1906 general election. Anti-Chinese legislation also began during this period, with Chinese seamen being the only group to be subject to a language test for employment.

In 1919, race riots erupted again throughout the U.K. targeting Arab, African, Chinese, West Indian and Indian peoples and repatriation committees were established in the cities of London , Cardiff, Glasgow, Hull to “rid” the country of these groups.

In the 1920s, the Home Office came close to forcefully deporting 1,100 Chinese seamen from Liverpool – but this was aborted at the last second to avoid international furore. By 1920, however, Chinatowns were emptied out due to lack of jobs – most Chinese went home voluntarily.

After World War Two, the government went as far as to forcibly repatriate thousands of Chinese seamen – many of whom made great contributions to the war effort. In some instances, the seamen were abducted on their way to the shops and packed off onto ships to China, unable even to say goodbye to their British families and Children. The government kept the forcible repatriations tightly under wraps for decades. In 2006, a plaque was unveiled in Liverpool commemorating the Chinese seamen who had once lived in the city.

Conclusion

Unearthing the past can be a painful process, especially when looking into your own family history. It’s important to be mindful of the impact that exclusionary policies and racism can have on your family members as this trauma can often be passed on from one generation to the next. Bear this in mind when you investigate your own family history. Knowledge is power, however, and acknowledging the difficulties of migration is often the first step in understanding the complexity of your family story.

Be inspired! Join Chinese family history community.

If you are interested in uncovering your immigrant ancestors’ history, we would love to be of assistance. Our global team of researchers has helped over 200 families discover their Chinese lineage. Get in touch for more info!

Thanks for featuring our Victorian CEDT Index. My fellow volunteers at the Chinese Australian Family Historians of Victoria and I thank you!

Thank you for sharing our Victorian CEDT Project. The volunteers from the Chinese Australian Family Historians (CAFHOV) and I thank you!

Thank you to you and the team, Kristy! 🙂

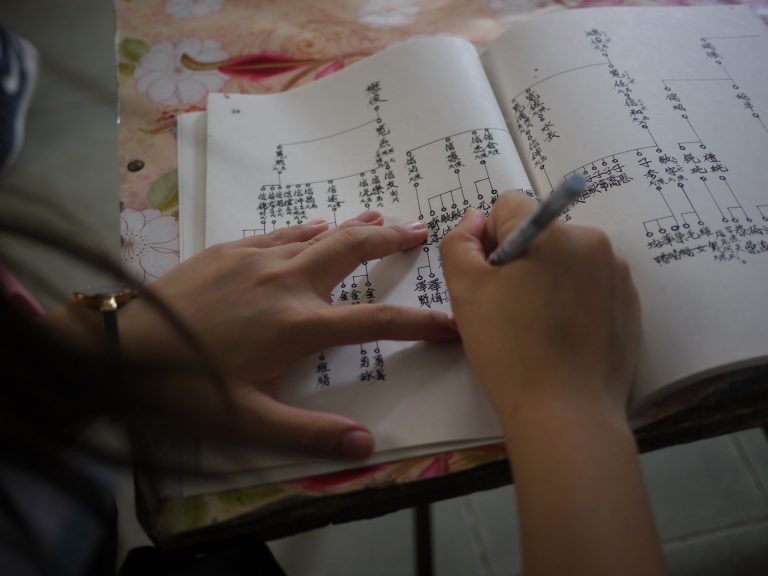

As an American born Chinese person, my great-grandfather emigrated to California in the late 1800’s. My grandfather then followed him by 1910 and settled in San Francisco before relocating to Los Angeles. I’m so thankful that he continued to document our family’s history in our Jai Pu and was provided the last documentation of our clan depicting his life and family of 13 children. This precious family journal reaches back 33 Generations and I have been given the task of updating our progression with the following 6 generations of American born Chinese known as The Guan Clan. To date we number just under 120 aunts, uncles, and cousins residing throughout the United States. I sincerely thank the staff and researchers at “My China Roots” for providing invaluable information as you have. As a family there are roughly 50 close relatives still residing in Los Angeles and we continue to remain close to one another. We still celebrate Lunar New Year, the Lantern Festival, Qingming, and of course Mid-Autumn Festival. Several of us have Home Alters where we pay homage to our ancestors by lighting incense and candles. Keeping our heritage alive and passing it on to the younger generation is our family pride!